LOS DIOSES NO ESTÁN EN LA NATURALEZA

(THE GODS ARE NOT IN NATURE) NN12.24 / LDNEELN08.19

LOS DIOSES NO ESTÁN EN LA NATURALEZA

(THE GODS ARE NOT IN NATURE) NN12.24 / LDNEELN08.19

NAMING NATURES

MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY OF NEUCHÂTEL

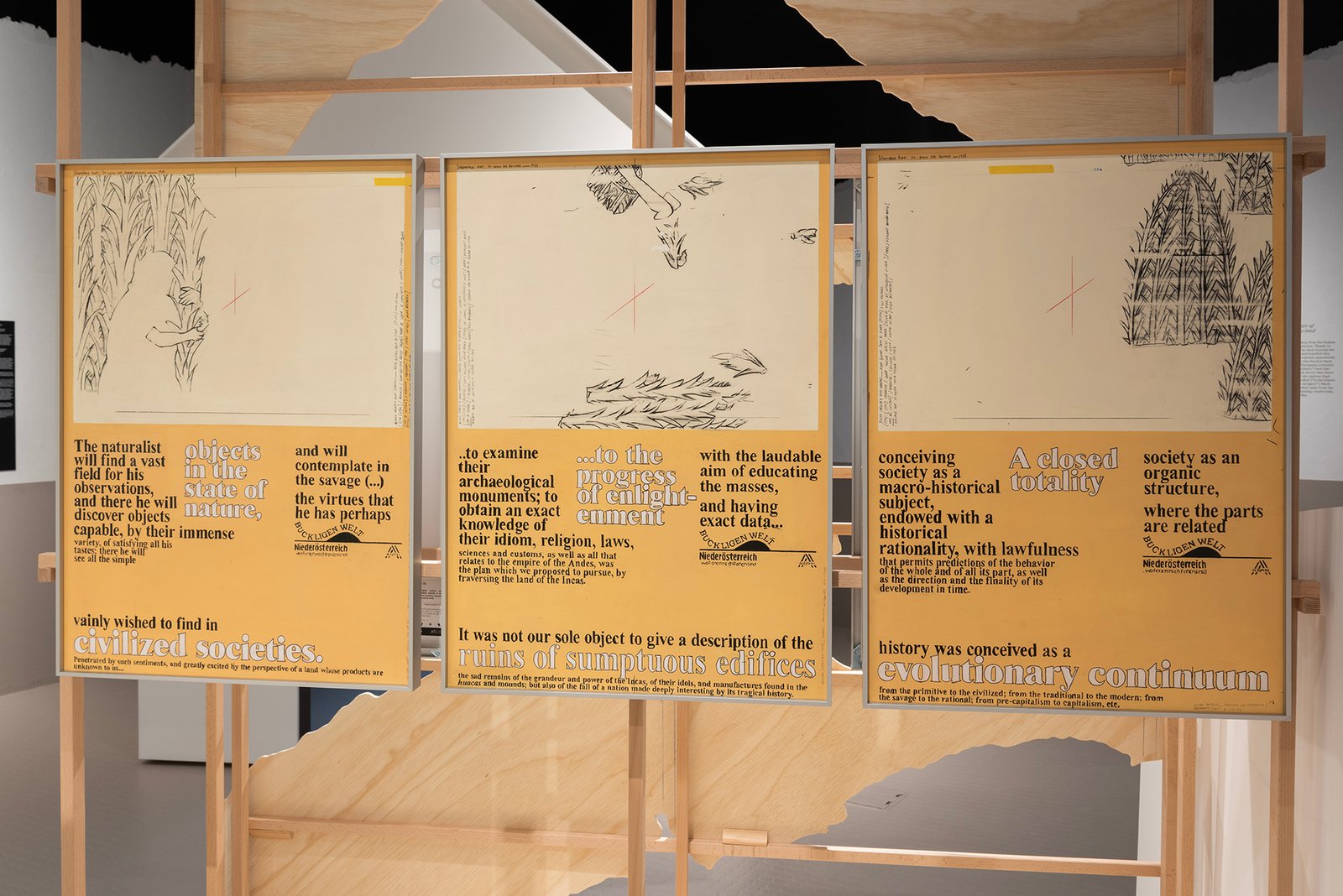

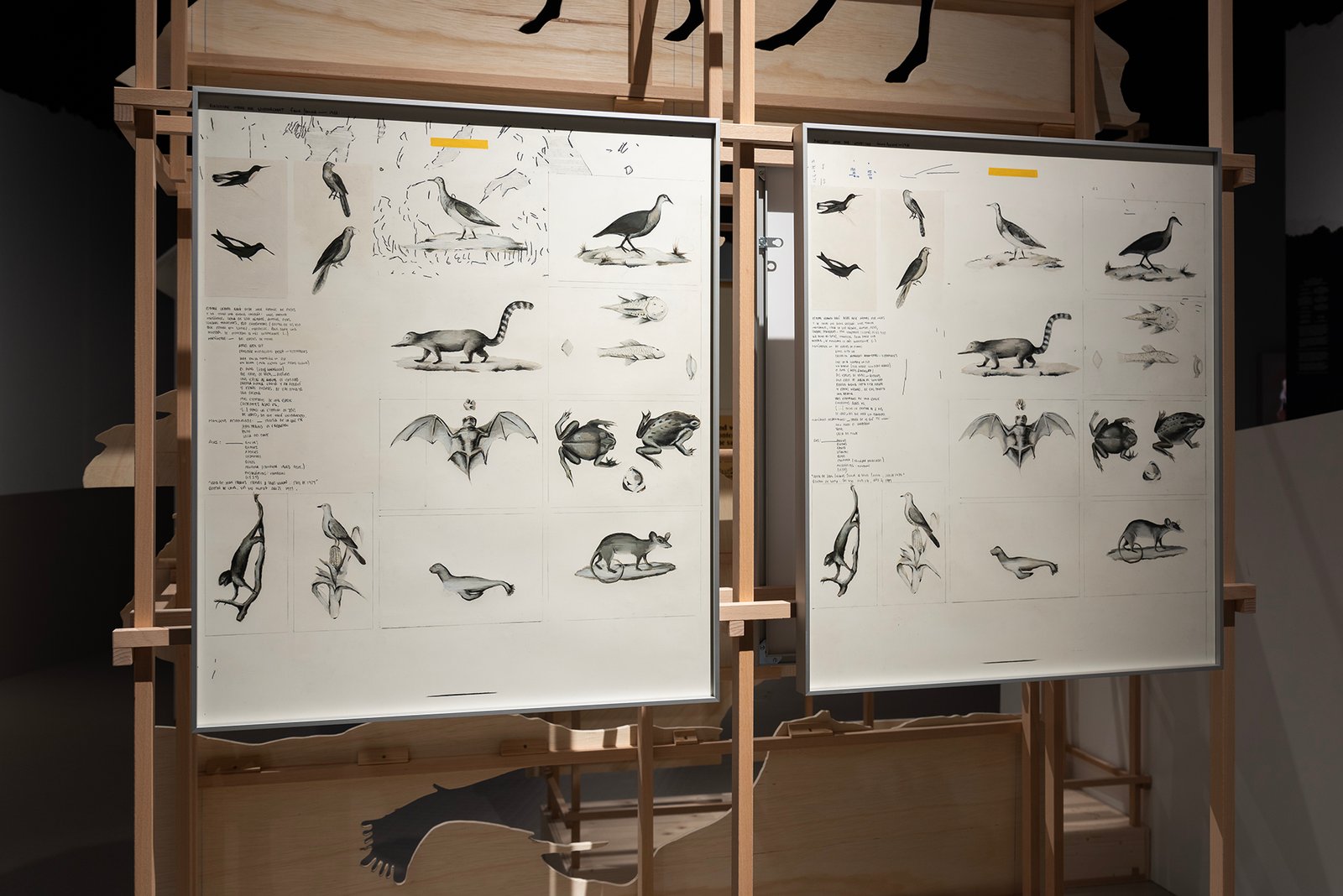

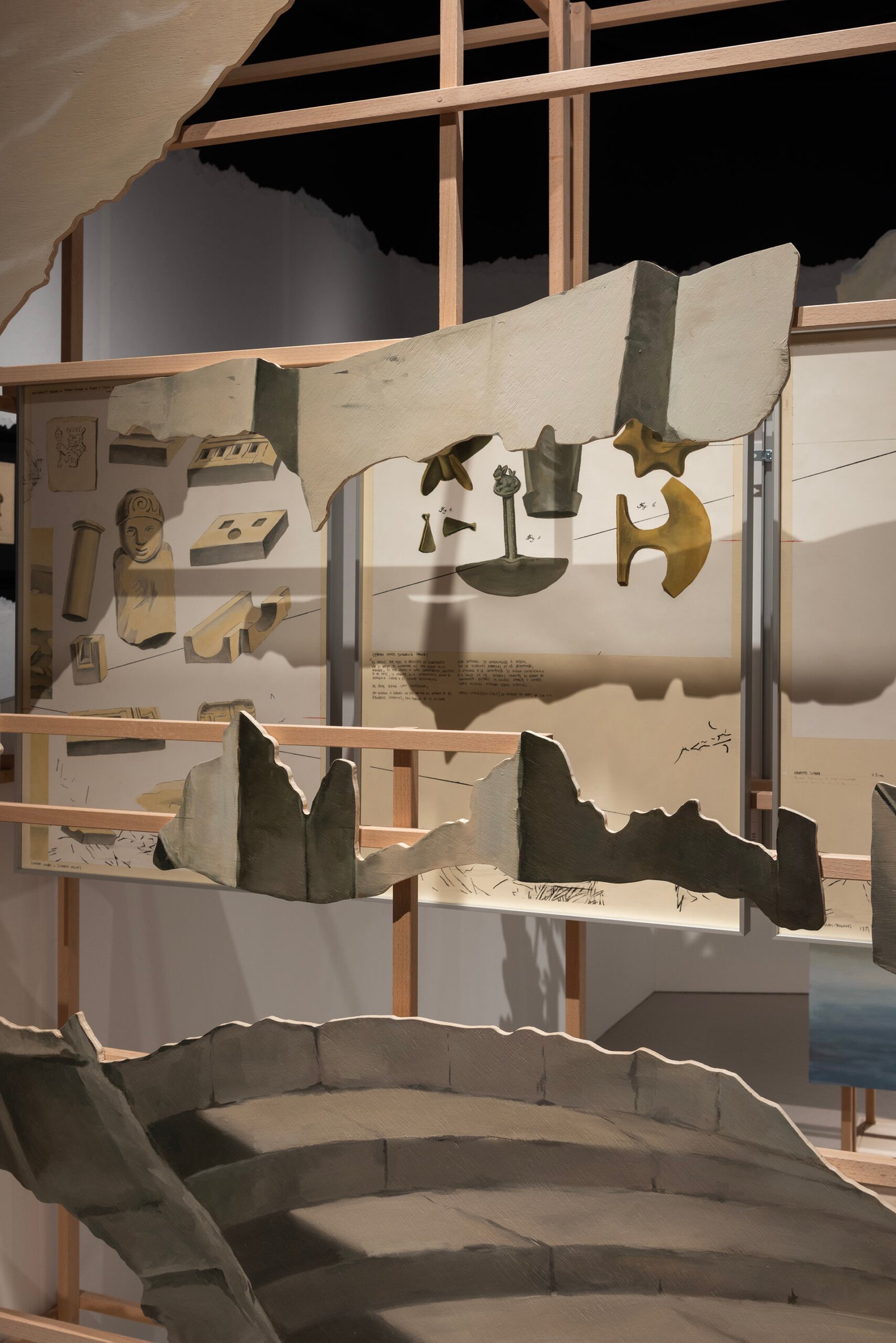

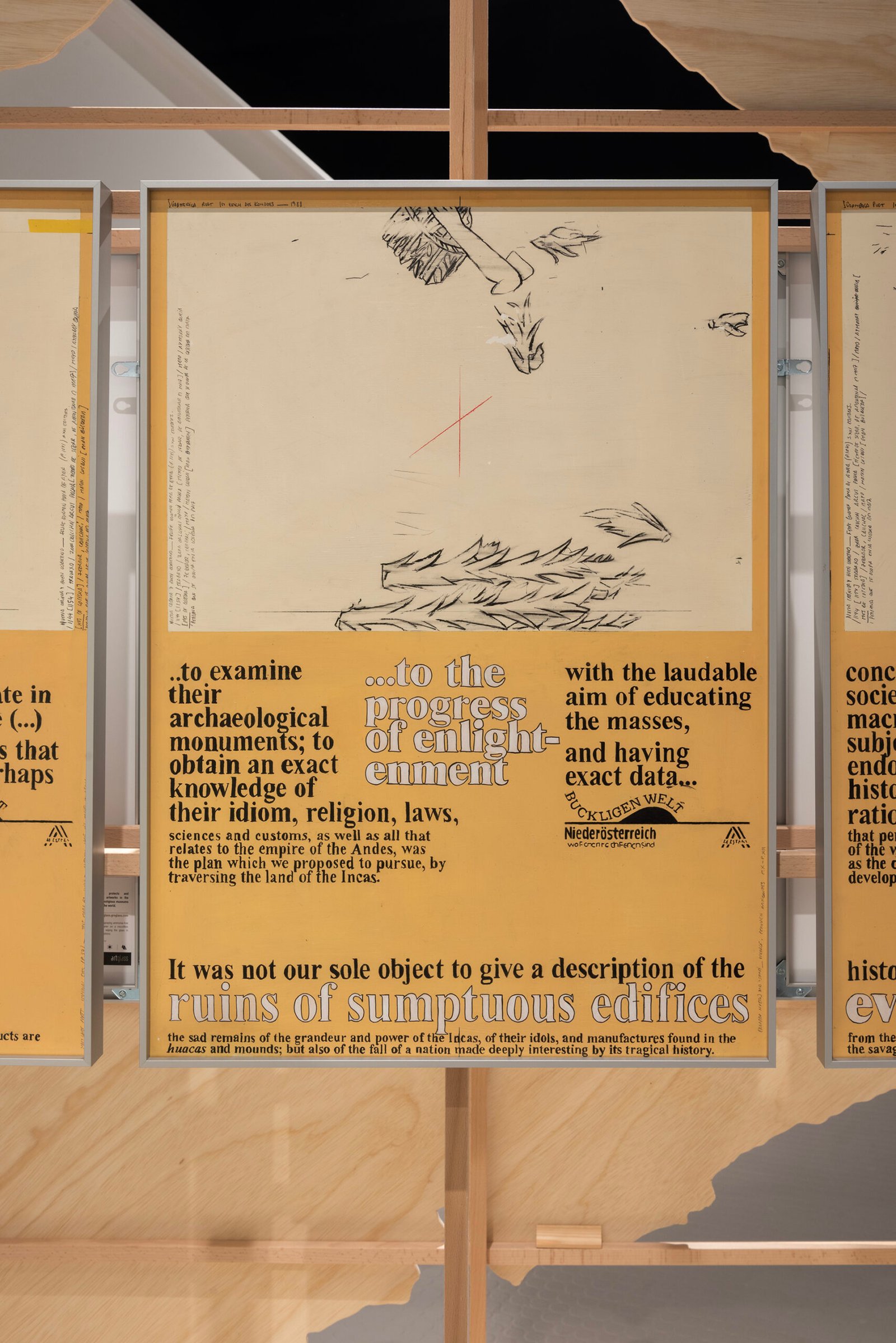

«The multi-site exhibition Naming Natures, co-curated by historian Tomás Bartoletti and artist-researcher Denise Bertschi in collaboration with the Natural History Museum in Neuchâtel (MHNN) and the Neuchâtel Centre d’Art (CAN), approaches the history of Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob von Tschudi and his zoological collections allocated in Neuchâtel. This ‘Helvetian Humboldt’ hunted more than six hundred specimens in Peru between 1838 and 1842, still preserved at MHNN. He also brought back archaeological artefacts and human remains, now housed in Swiss and European institutions. The art-science exhibition shows Tschudi’s collection for the first time in its entirety, together with hundreds of documents and objects found in several museums and libraries in Switzerland, Austria and Peru.»*

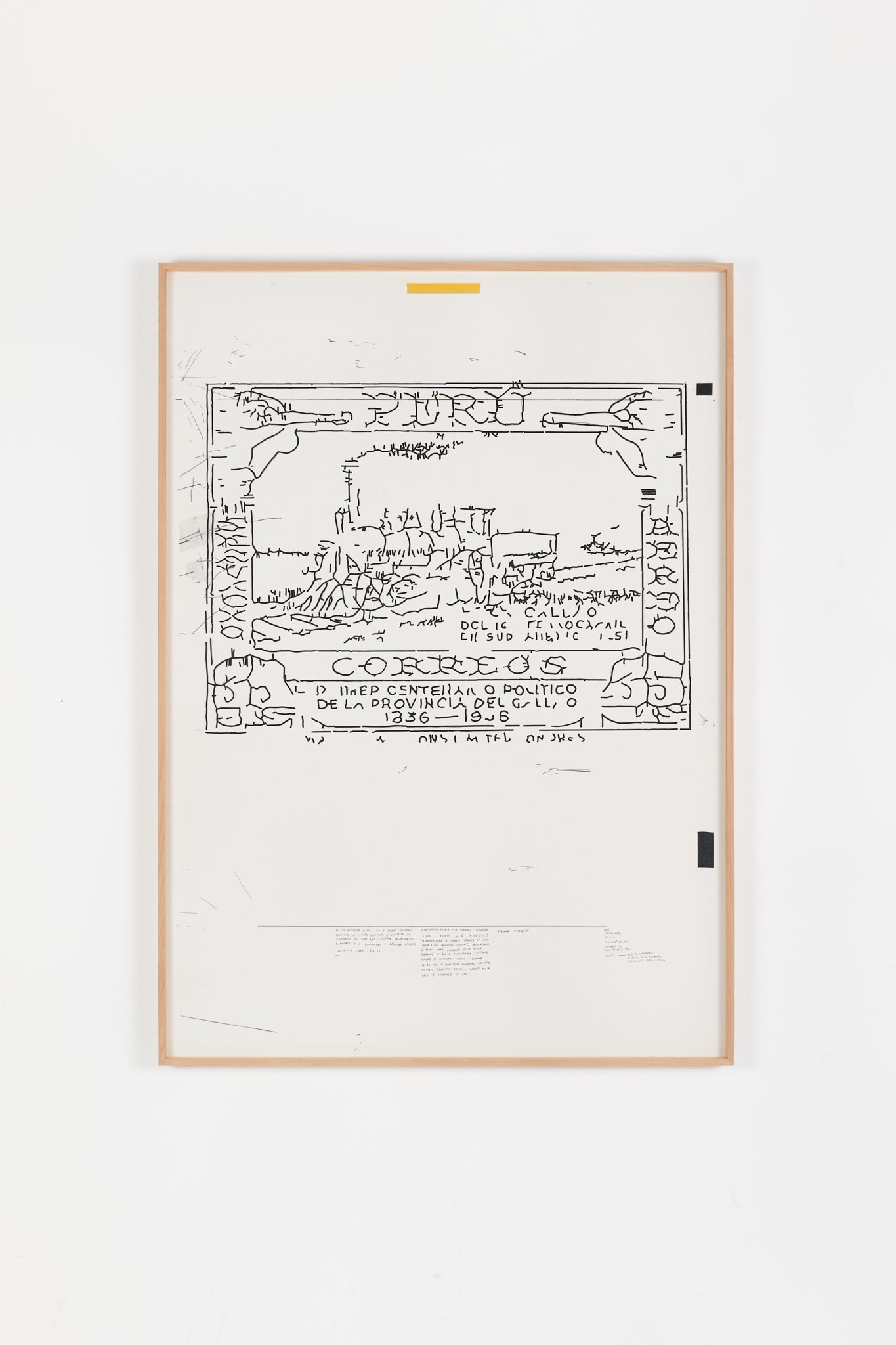

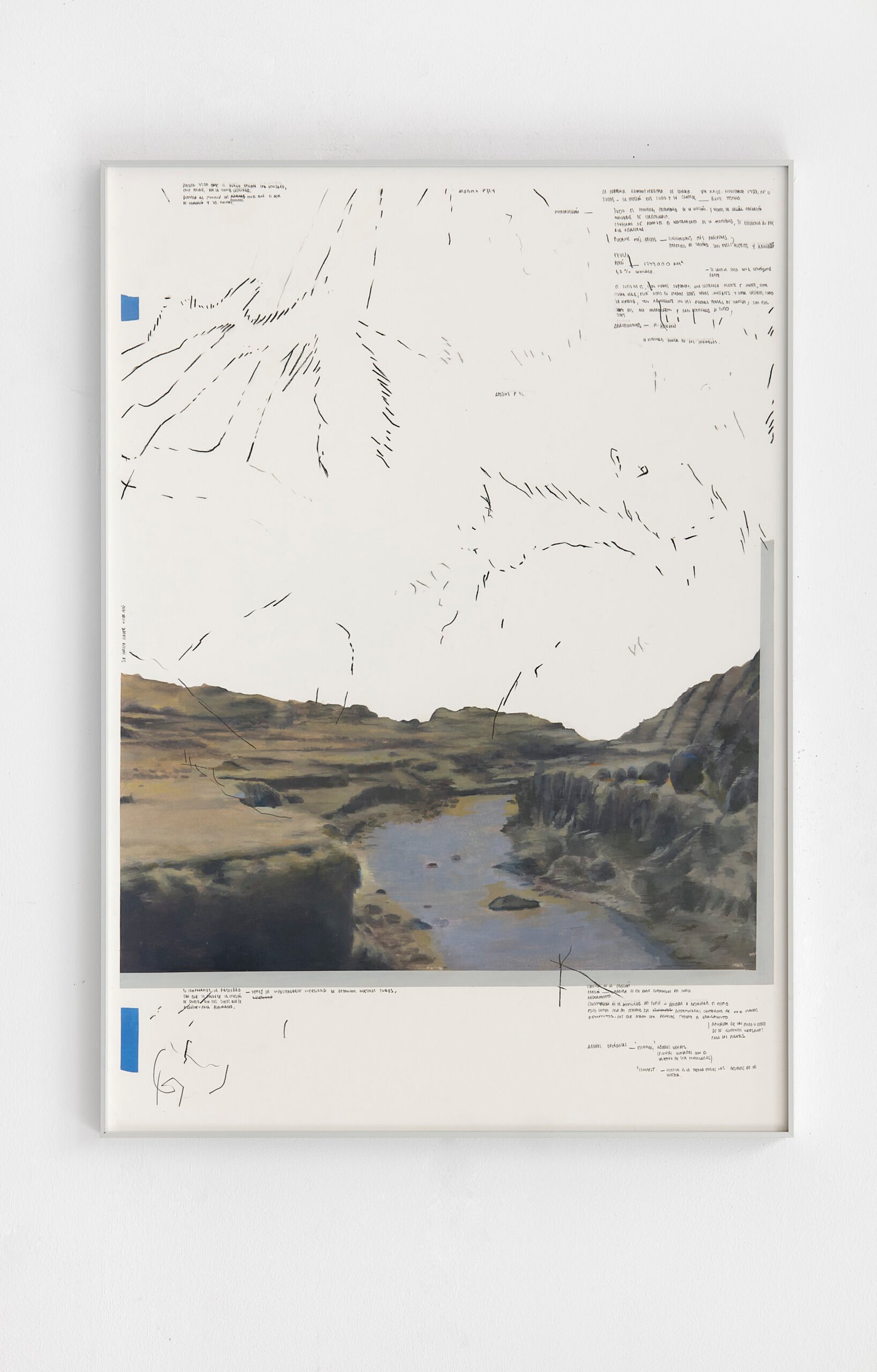

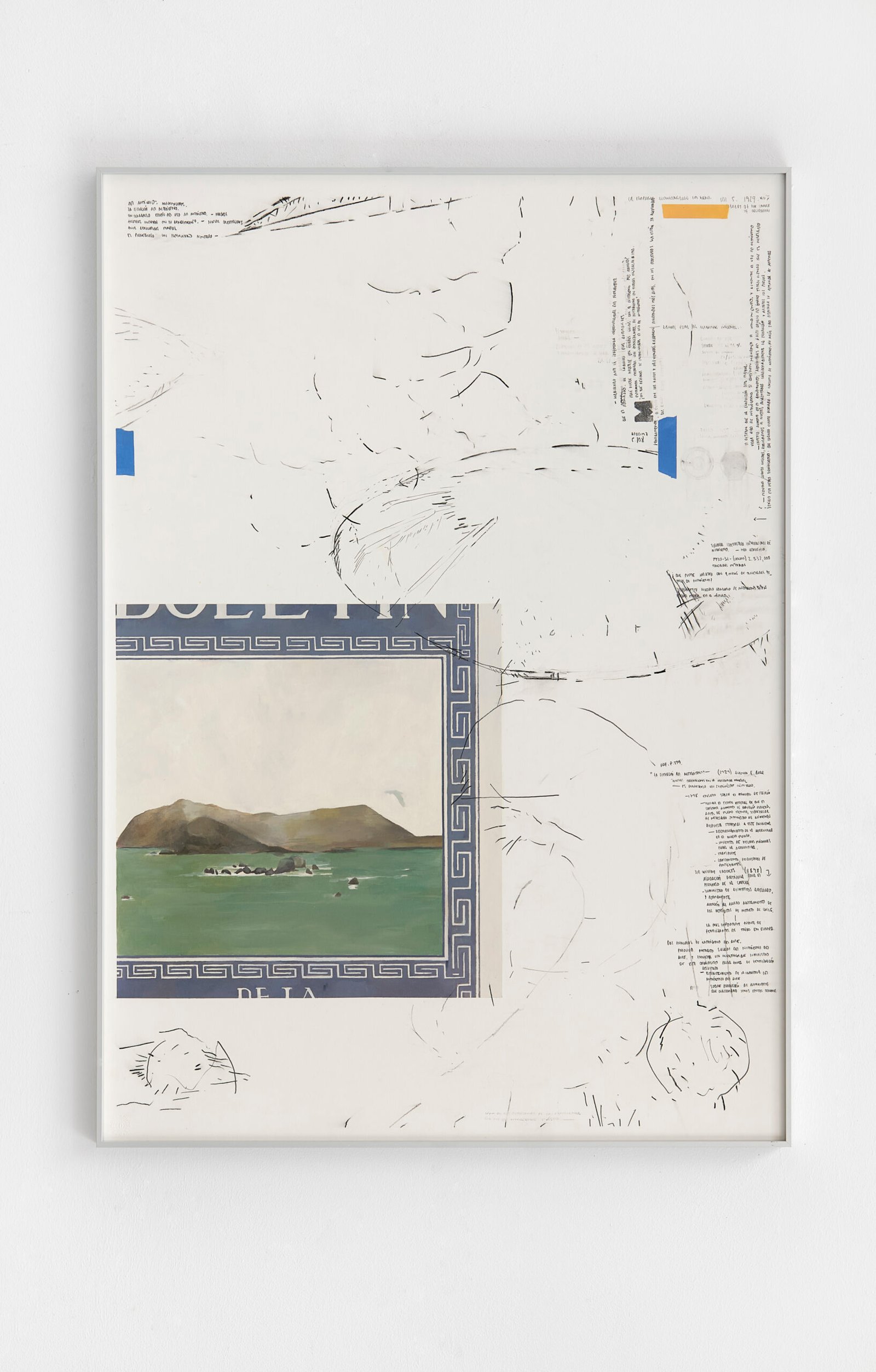

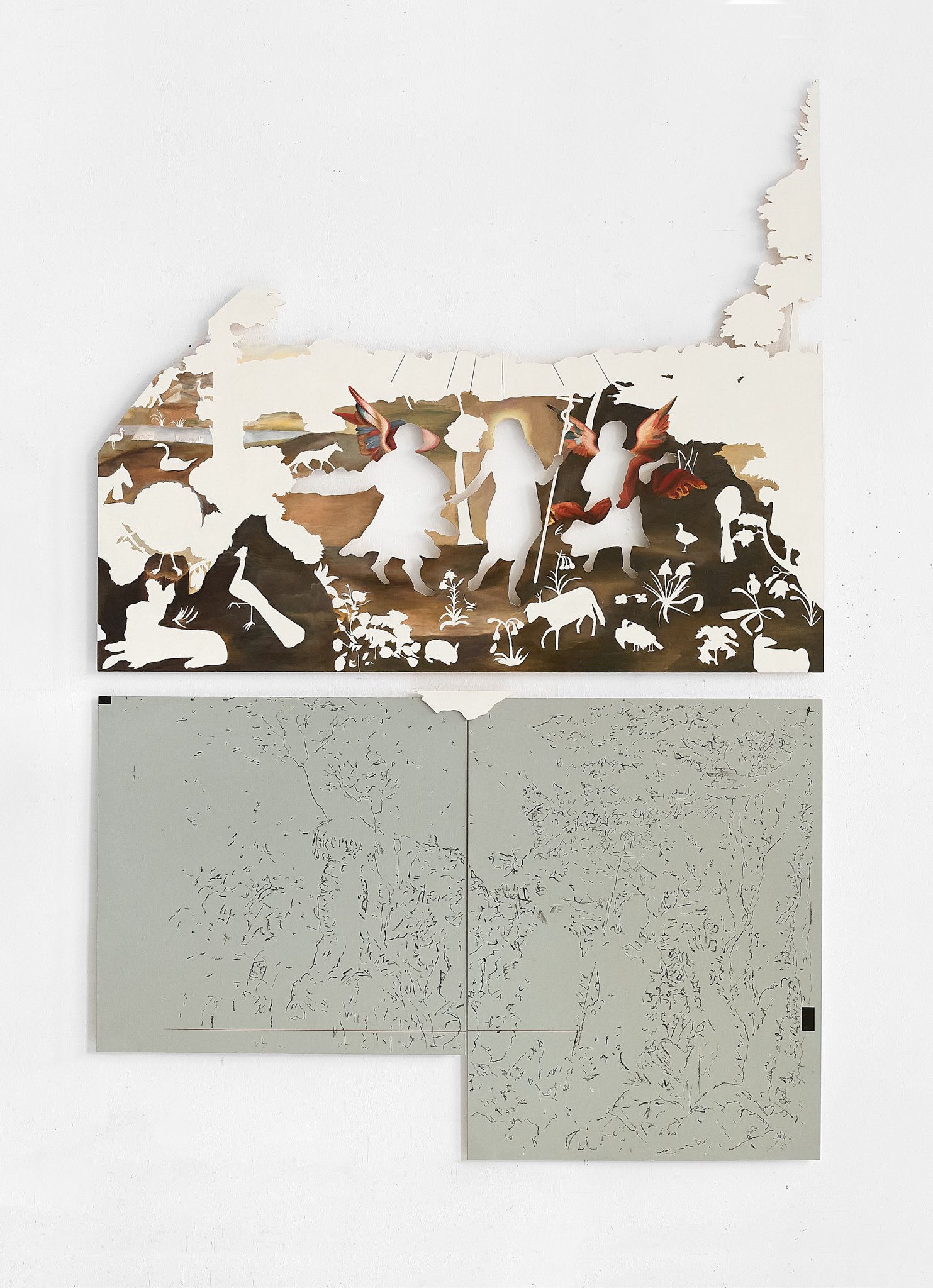

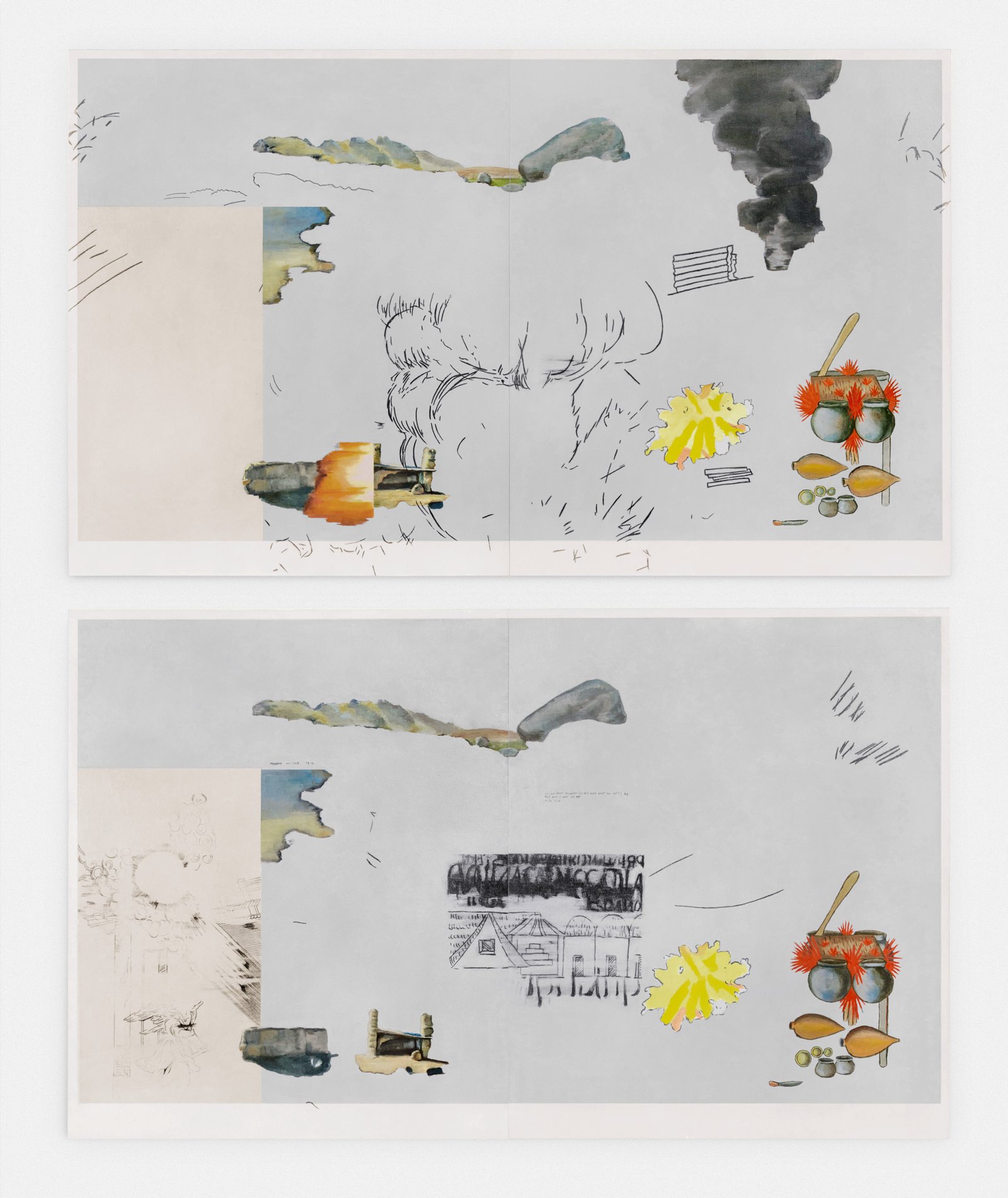

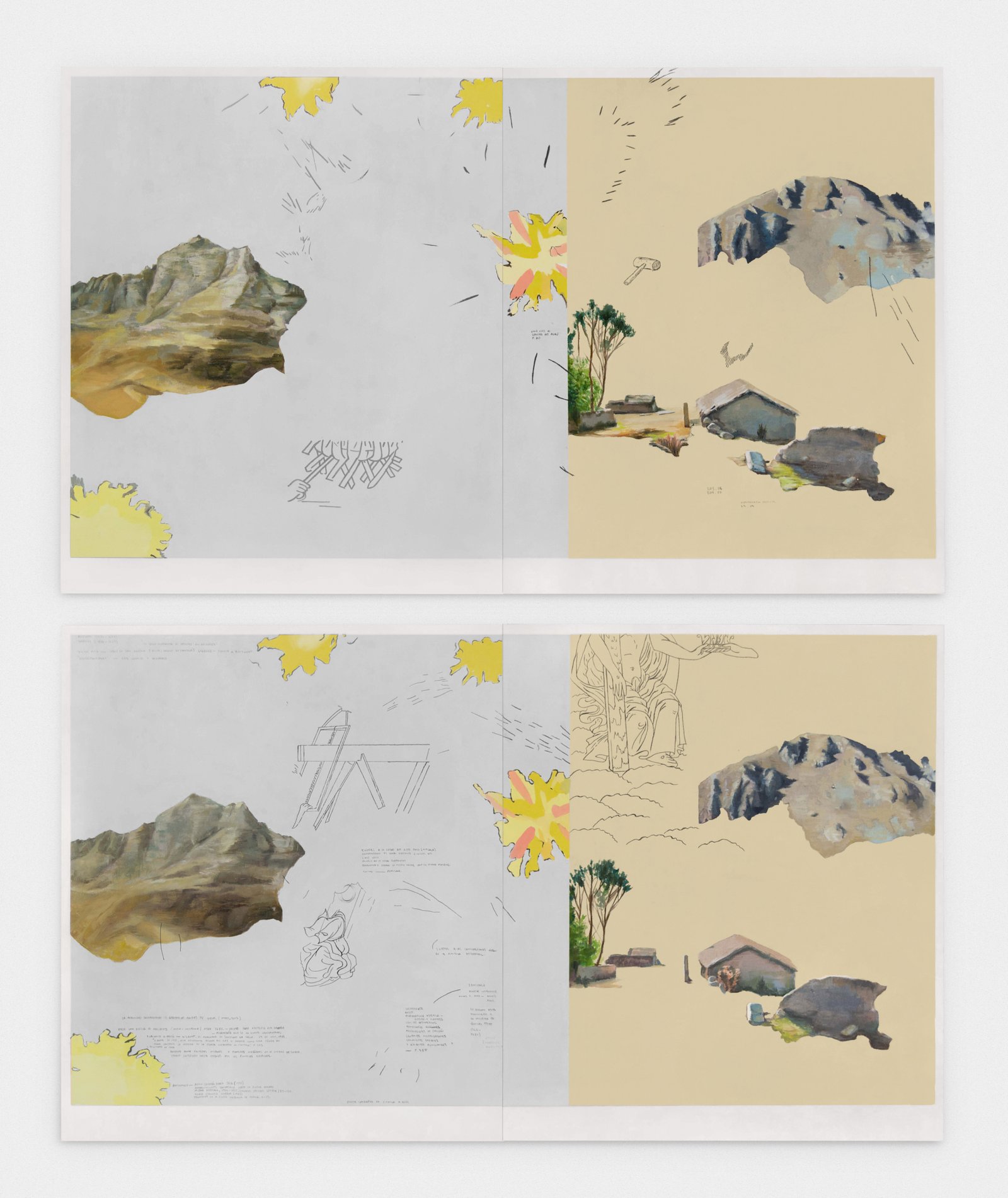

NN1.0624 and NN2.0624 are center on the construction of scenic scale model panels based on lithographs from the book Antigüedades peruanas (1859) and Fauna peruana, both researchses of the Swiss naturalist Johann Jacob von Tschudi.

The use of scenography as a resource seeks to present the false and flat backdrop of a constructed reality, as a way of metaphorically thinking about how a specific organization of elements in the world (a context) is conveyed through a form of representation; drawing from the idea of scenography as fiction. On the reverse of these scenic panels are images referring to the aesthetic imagination behind the categorization and rationalization of this pre-Hispanic culture, using archival materials from the MHNN’s informational panels and graphics, together with critical approaches drawing from diverse textual references.

*Fragments taken from the curatorial text.

Production process credits:

Dextre Polo, Sofia Nakasone.

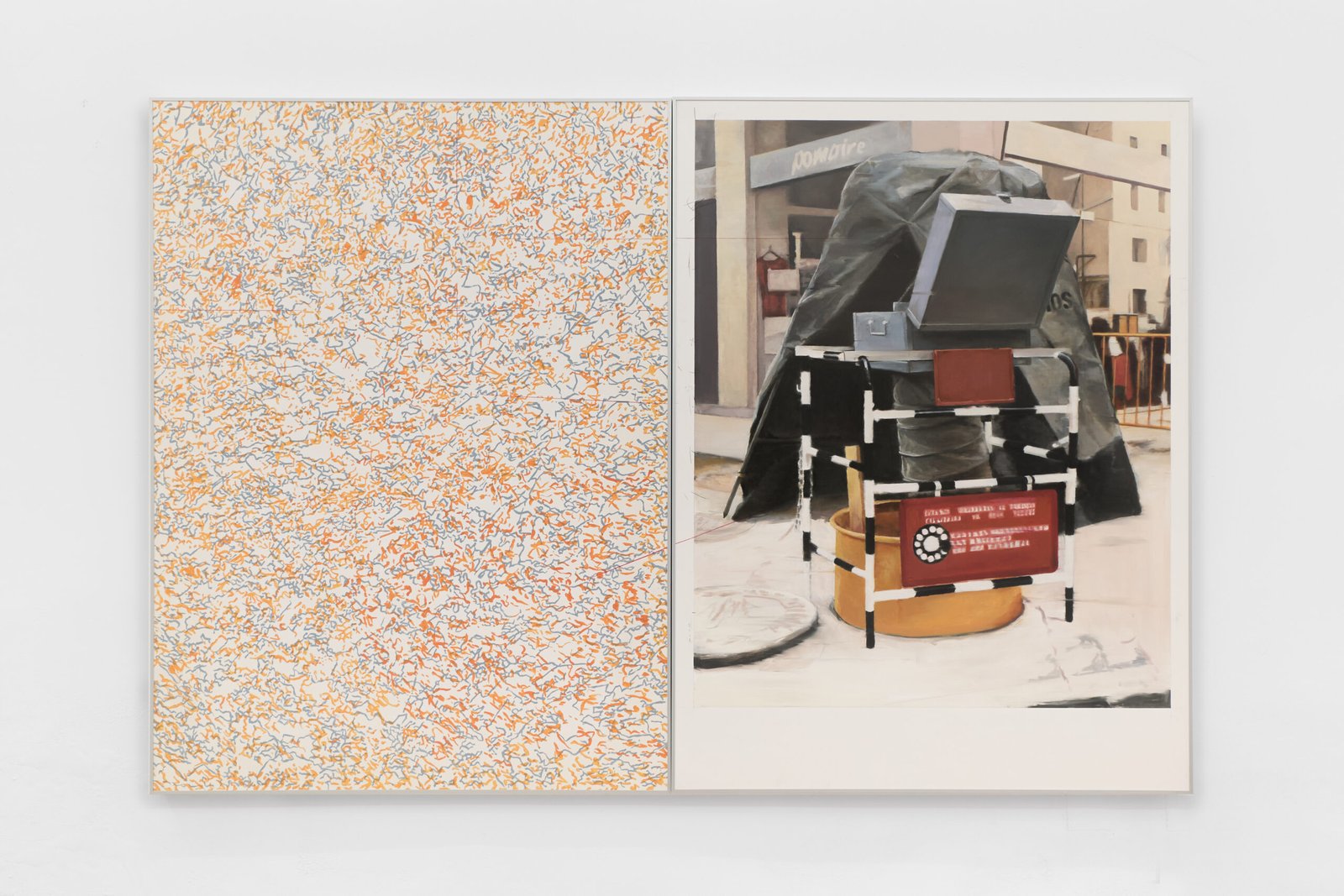

NN12.24

Exhibition views of Naming natures. Photo credits: Remy Ugarte

Details

Details

Untitled (from the Series NN1.0624 and NN2.0624)

Oil and graphite on paper

142x280 cm

2024

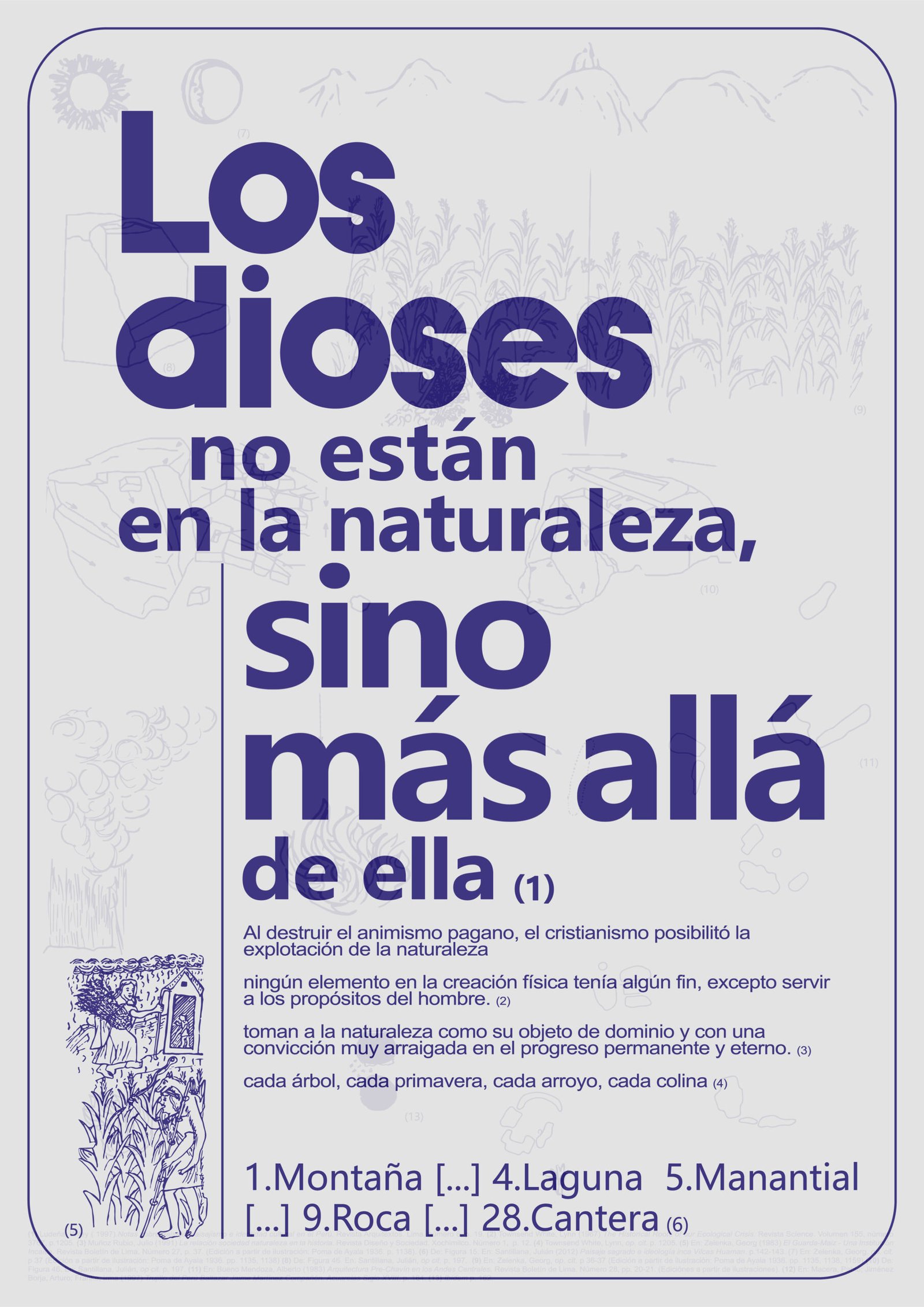

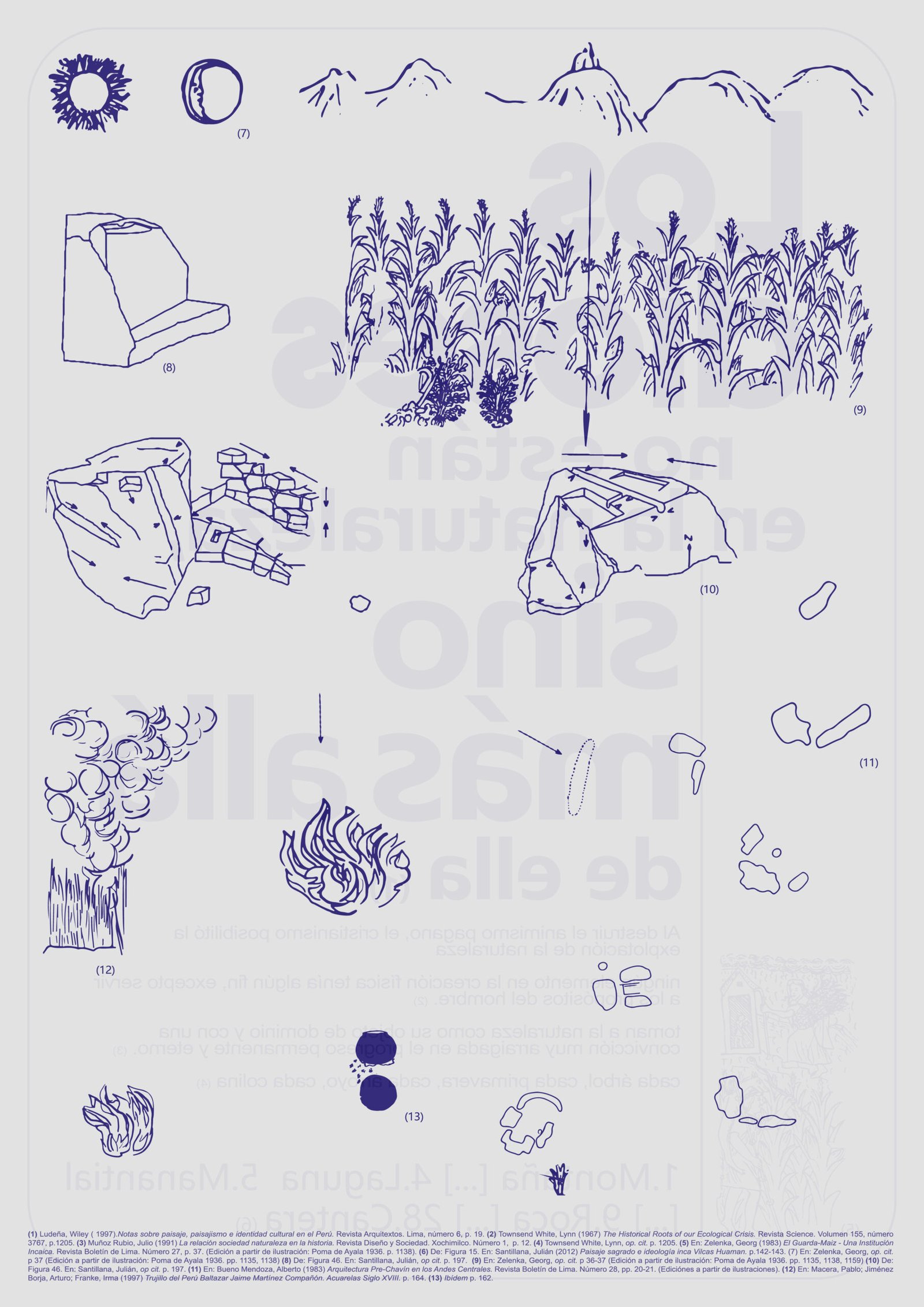

LOS DIOSES NO ESTÁN EN LA NATURALEZA

ICPNA San Miguel

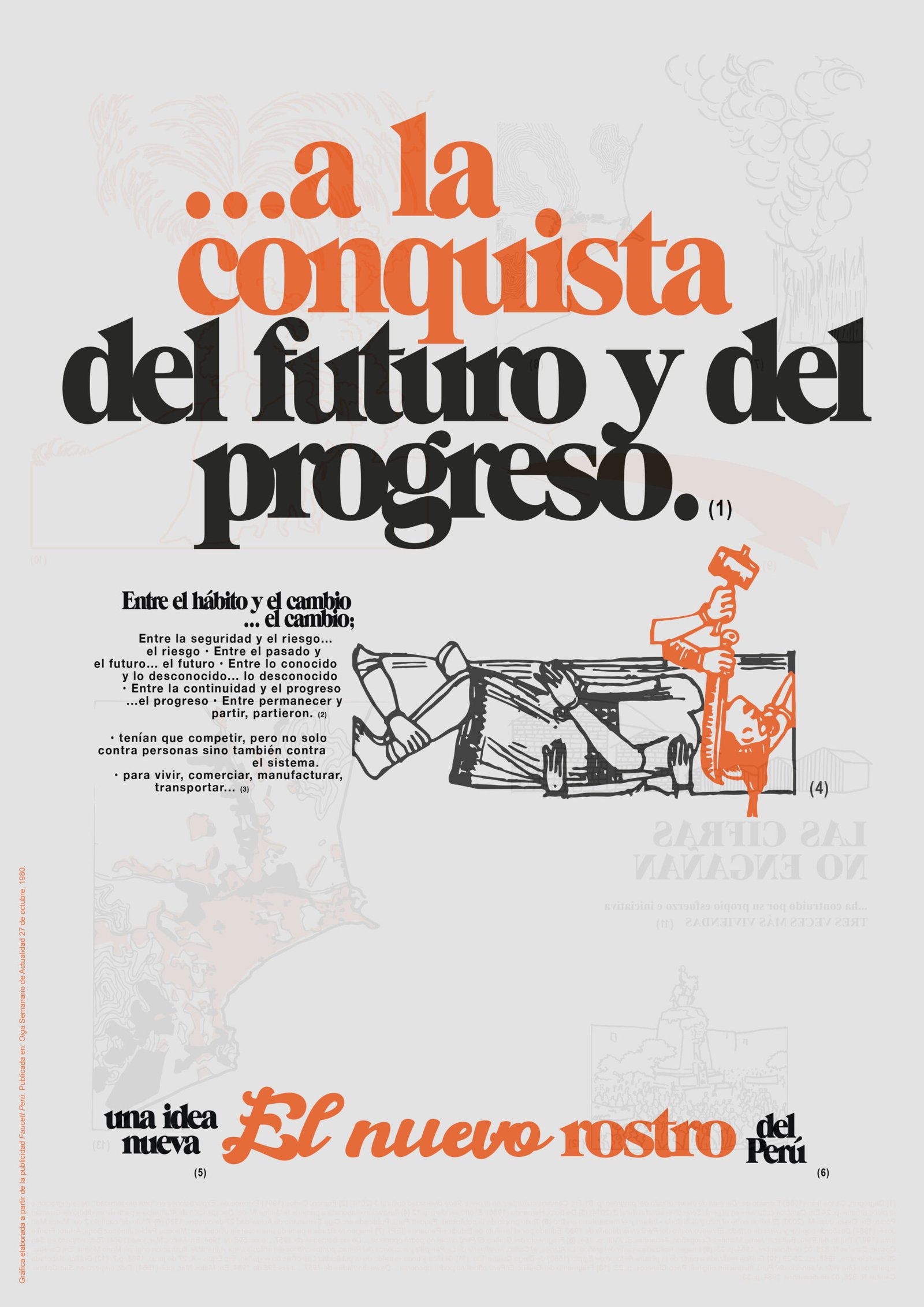

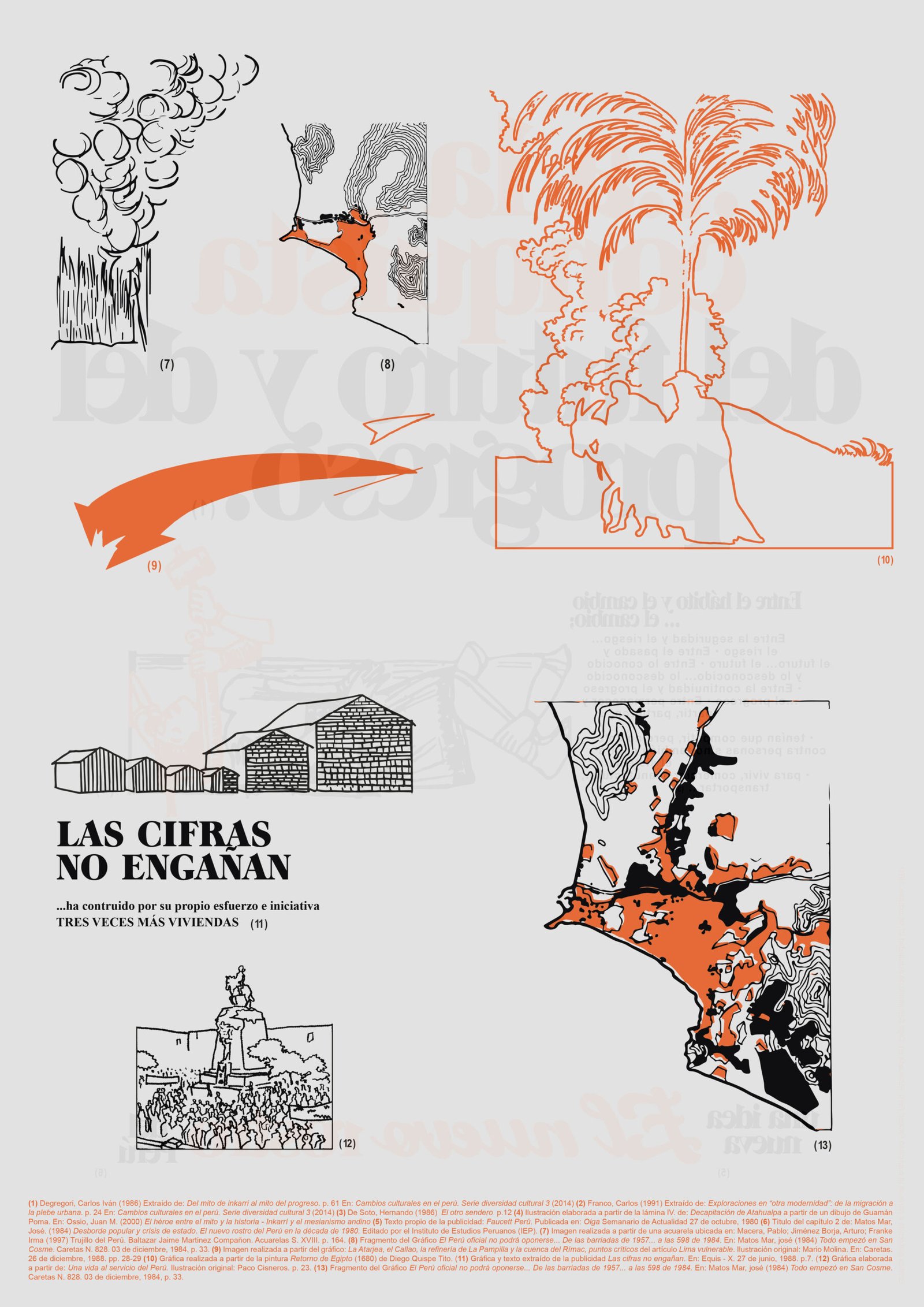

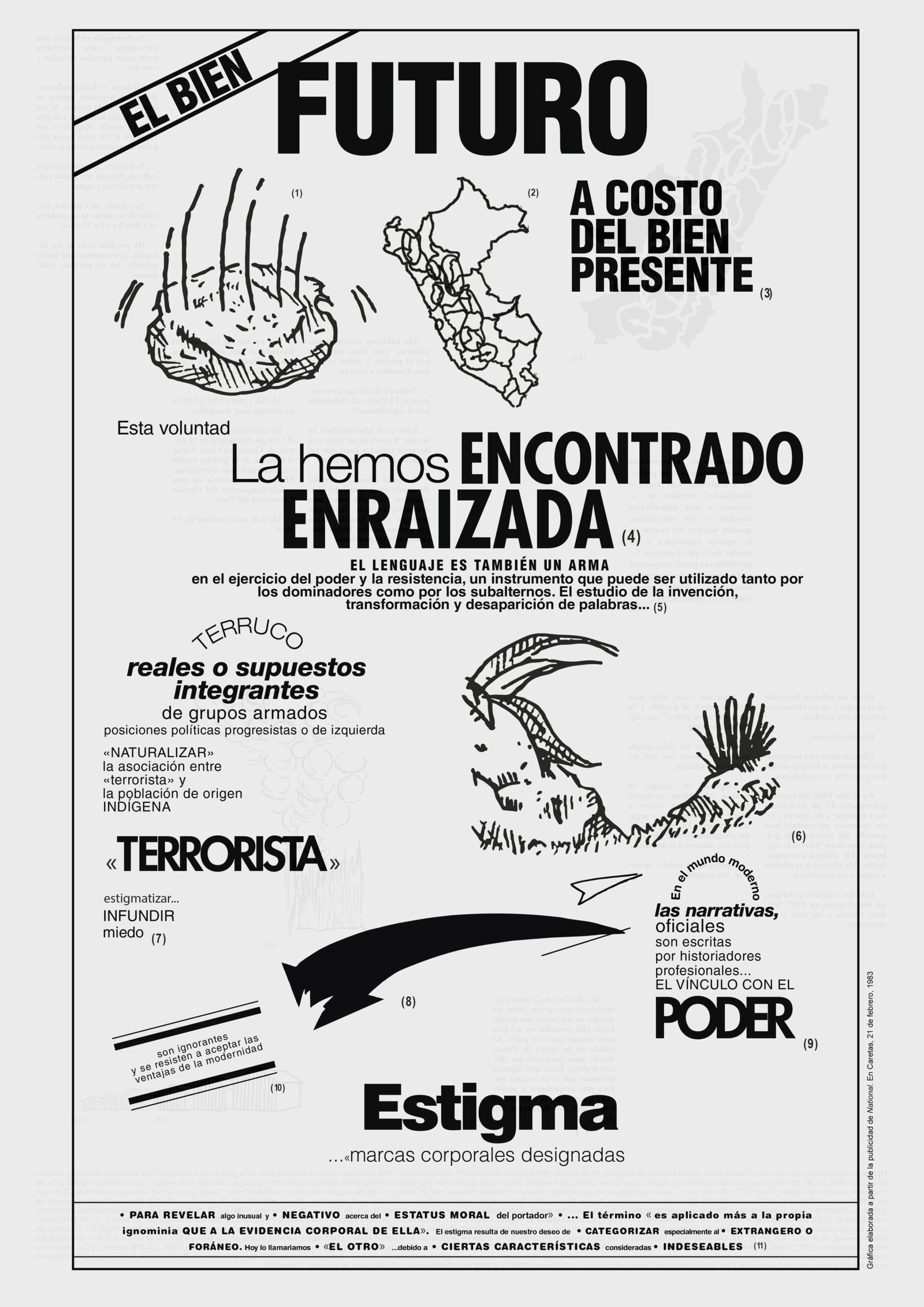

The literary word, as a unit, is unstable; it corresponds to a sociocultural structure that determines its meaning and transforms it. Following this, a text becomes a crossroads of textual surfaces: multiple writings where the meaning is given not only by its independent and contextual meaning, but by its use in history: its past meanings, its authors, its addressees. The intertext is just that: constituted by a set of multiple quotations, identifiable, connected in a non-linear way in the present and finally expressed in a circular way in time.

Under these conditions, I think about the possibilities that exist when applying the meaning of this concept (intertextuality) to an image from a nominal character. I was interested in reviewing the historical conditions that have produced certain types of images and how a look from the present changes their meaning.

. . . .

“(…) the gods are not in nature, but beyond it” is a fragment taken from a text by architect Wiley Ludeña (Notas sobre el paisaje, paisajismo e identidad cultural en el Perú, 1997) where he paraphrases and recontextualizes Lynn White’s approach (in The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis, 1967) on the process of evangelization and how it affected man-nature relationship. This slogan that erupts during the colonization process becomes an imperative that distances the indigenous people from the divine cult of nature, directing them to a position of domination and domestication of their natural environment. This will perhaps be a historical milestone to address a separation between countryside-city, nature-civilization and the socio-cultural changes and ideological divisions that occurred in later years in relation to the ideas of progress and modernity in the Peruvian context. In this project I seek to establish a tension between the imagination of the rural and the urban, traversed by the idea of progress and modernity from the use of the territory and its exploitation.

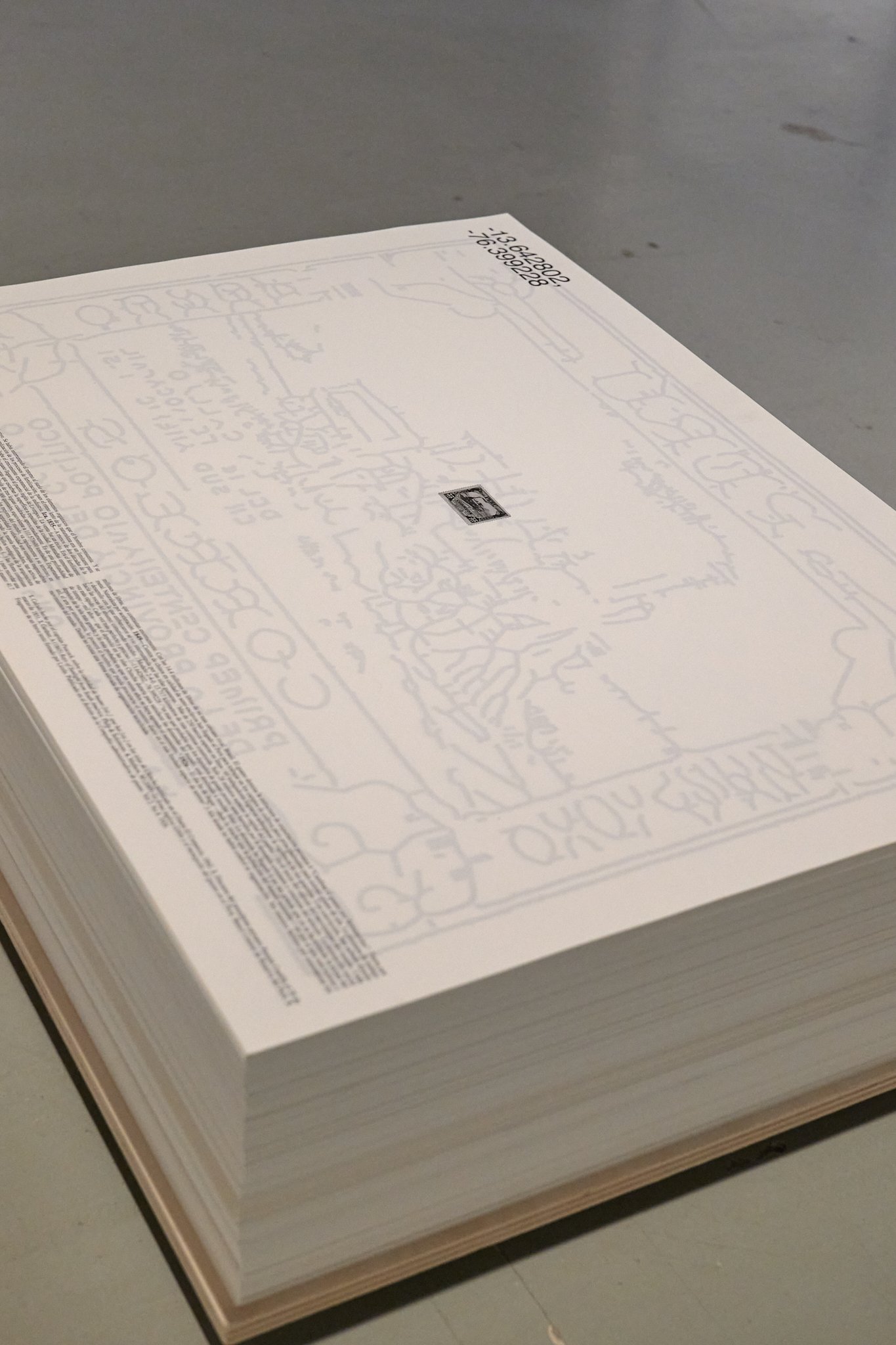

All the visual and textual information present in the exhibition has been produced from the transcription, recording and reproduction of physical and virtual archives; all of them reproduced to scale with a team of people, premeditatedly omitting certain visual or textual information.

All the images selected are representations associated with the Peruvian territory made from the 17th century to the present day.»*

*Fragments taken from the curatorial text.

Production process credits:

Diana Arteaga, Marysol Nanfuñay, Sofia Nakasone, Analuna Velarde, Dextre Polo, Olenka Macassi, Miguel Angel Polick.

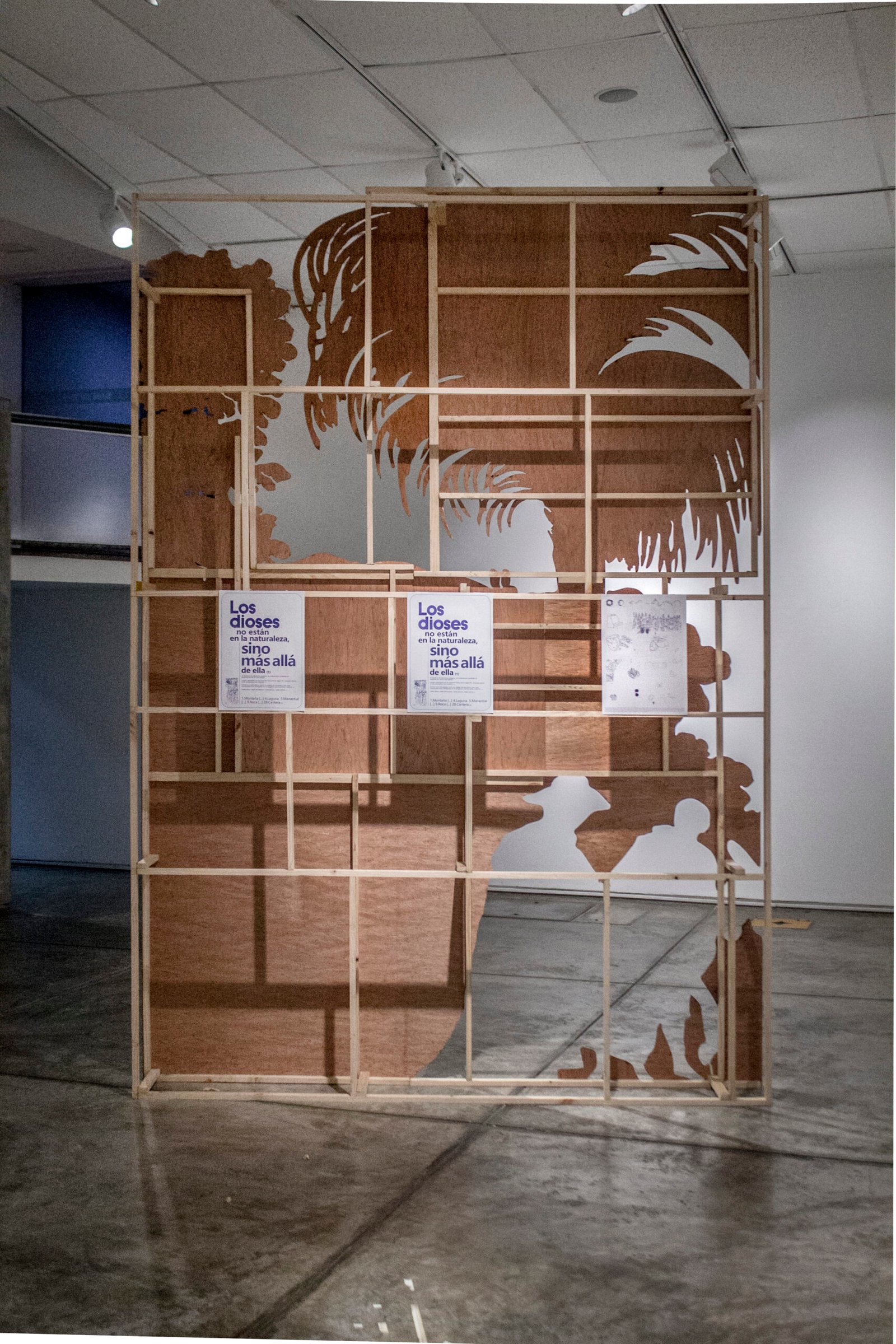

LDNEELN08.19

Exhibition views of Los dioses no están en la naturaleza. Photo credits: Celia Cueto

A la conquista del futuro y el progreso

Offset print

60x42 cm

2019

El bien futuro

Offset print

60x42 cm

2019

Los dioses no están en la naturaleza

Offset print

60x42 cm

2019

Untitled (Scenary 2) (Front)

Oil on wooden structure and offset prints

355x240 cm

2019

Untitled (Scenary 2) (Back)

Oil on wooden structure and offset prints

355x240 cm

2019

Los dioses no están en la naturaleza

Oil and graphite on paper

150x210 cm

2019

MÁQUINA FUSIONADORA

(FUSING MACHINE) ADIE06.25 / MC05.25 / MF03.25

MÁQUINA FUSIONADORA

(FUSING MACHINE) ADIE06.25 / MC05.25 / MF03.25

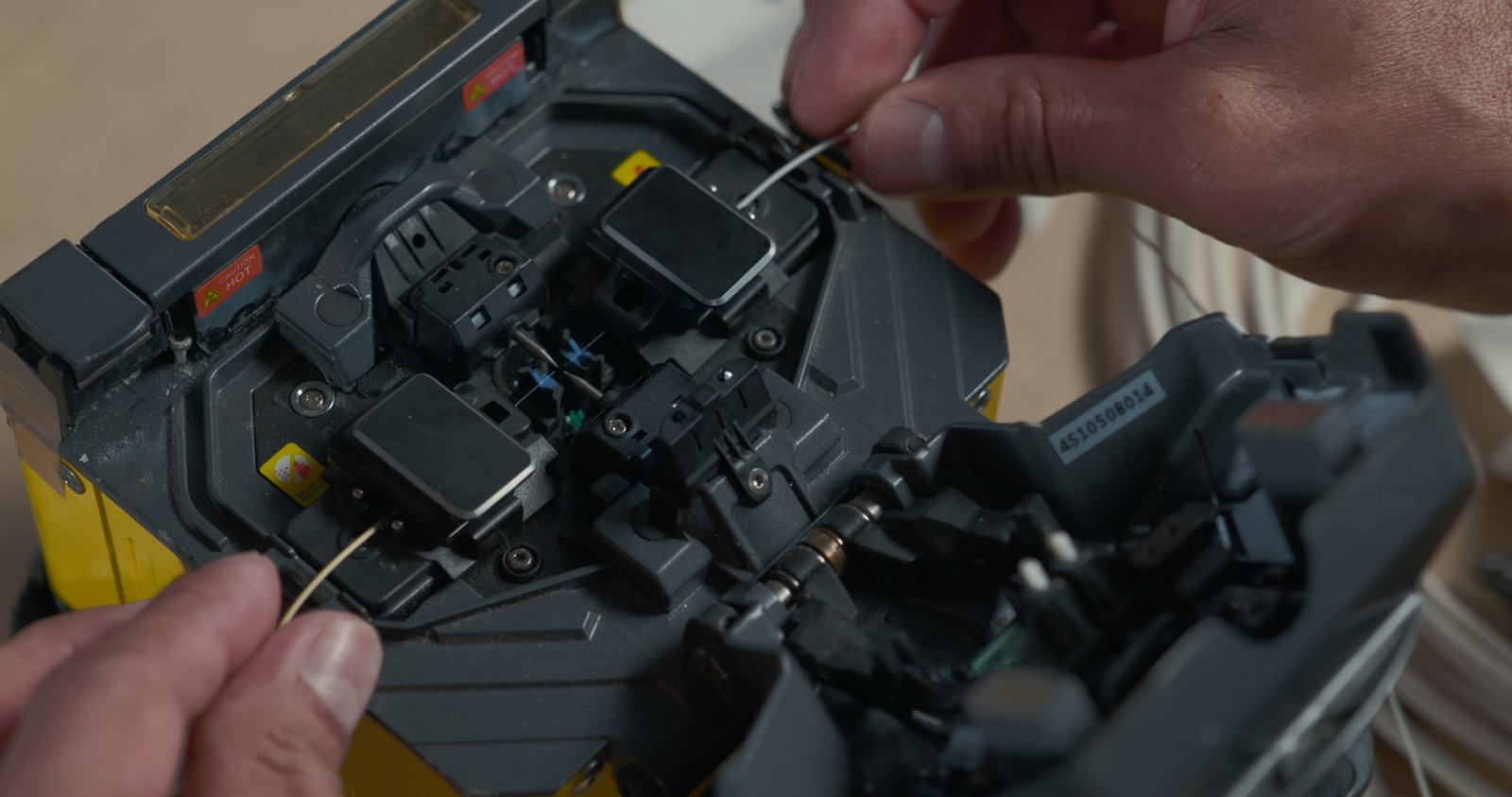

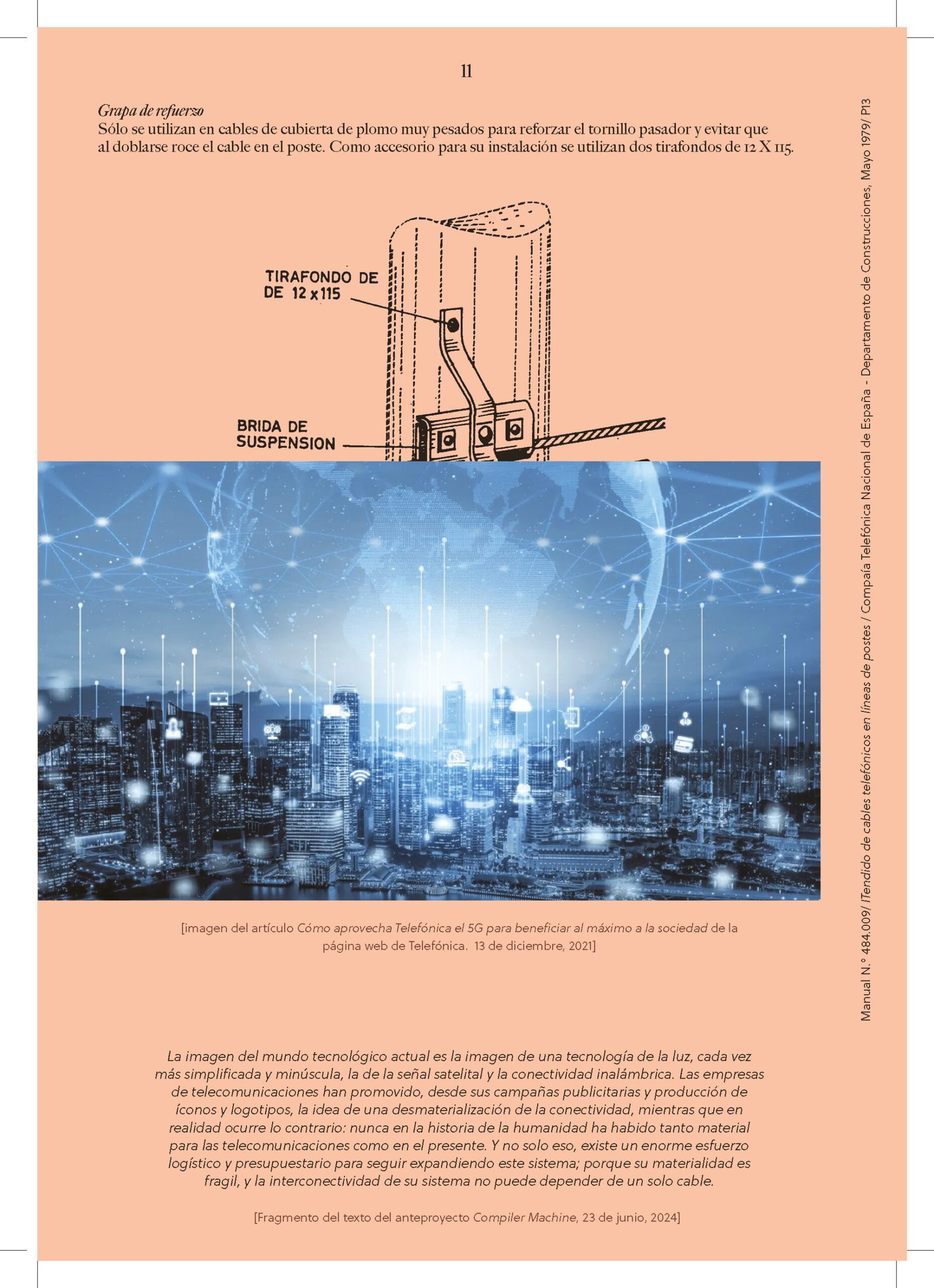

The flow of information has become a fundamental medium for defining the spatial and temporal relations of contemporary society. And while logistics centers are optimized and the means of distribution and vector data triangulation are systematized, the relationships between people, and their affective bonds mediated through material consumption and the instant exchange of messages and images, are also being transformed. Despite these technological advances, our devices are becoming increasingly smaller, and our imagination of the future seems to point toward a dematerialized reality, where possibly our voices (or perhaps our minds) will be connected without the need for an object to mediate between them. These ideas are also fueled by advertising that seeks to consolidate the rhetoric of the wireless and the cloud, and to promote a vision of interconnectivity associated with light, waves, and outer space. However, what sustains that imagination is nothing like an ethereal cloud or an aerial flow of light, but rather a vast material and human deployment: over a million kilometers of fiber-optic cable laid beneath the ocean, and another immense and incalculable amount buried underground and running through the walls of our homes.

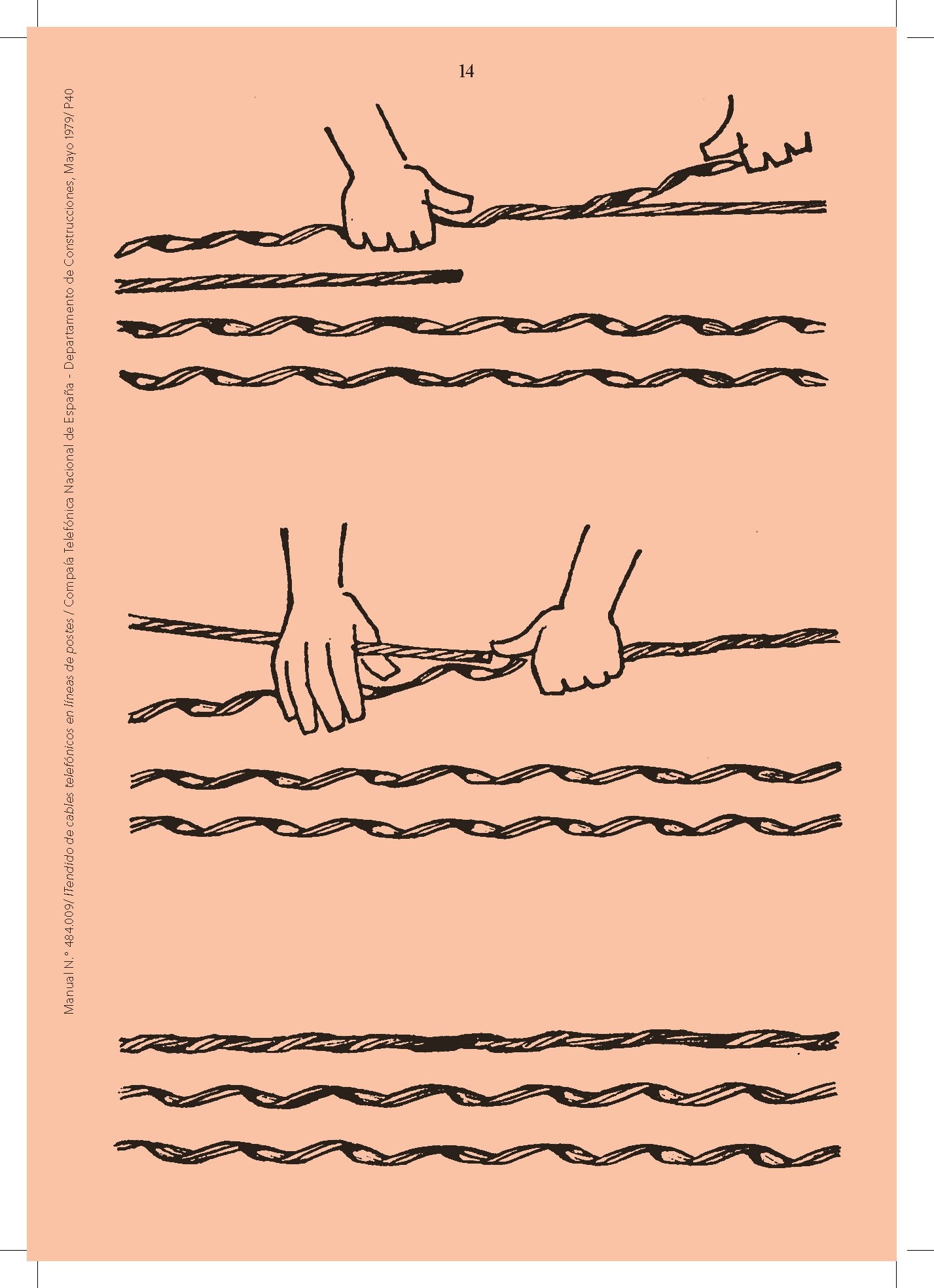

Because of this, thousands of workers spend day and night repairing constant cable breaks; their mission is to sustain the infrastructure and fuse a network that cannot lose continuity. They repeat the same operation countless times, each assigned to a different area of the world. Moreover, in their work, the role of technique and corporeality has taken center stage. Through their labor, their bodies have learned to measure the precise pressure to apply with the cutting tool in order to open the cable’s sheath without damaging it. Their touch allows them to distinguish kevlar from the plastic coating and even to sense when the cut at one end of the fiber may have been poorly made. In their work, as in any technical labor, bodily sensitivity is essential to accelerate the functions embedded within the chain of digital and mechanical operations that make global interconnectivity possible. Their role, therefore, must remain in sync and under control to ensure the delivery of quantifiable and predictable results. Yet, despite the importance of their labor, the system seems to condemn them to invisibility, sustaining the fiction of an almost organic social and technological growth—one that disregards material reality and makes it seem as if our destiny were naturally oriented toward progress.

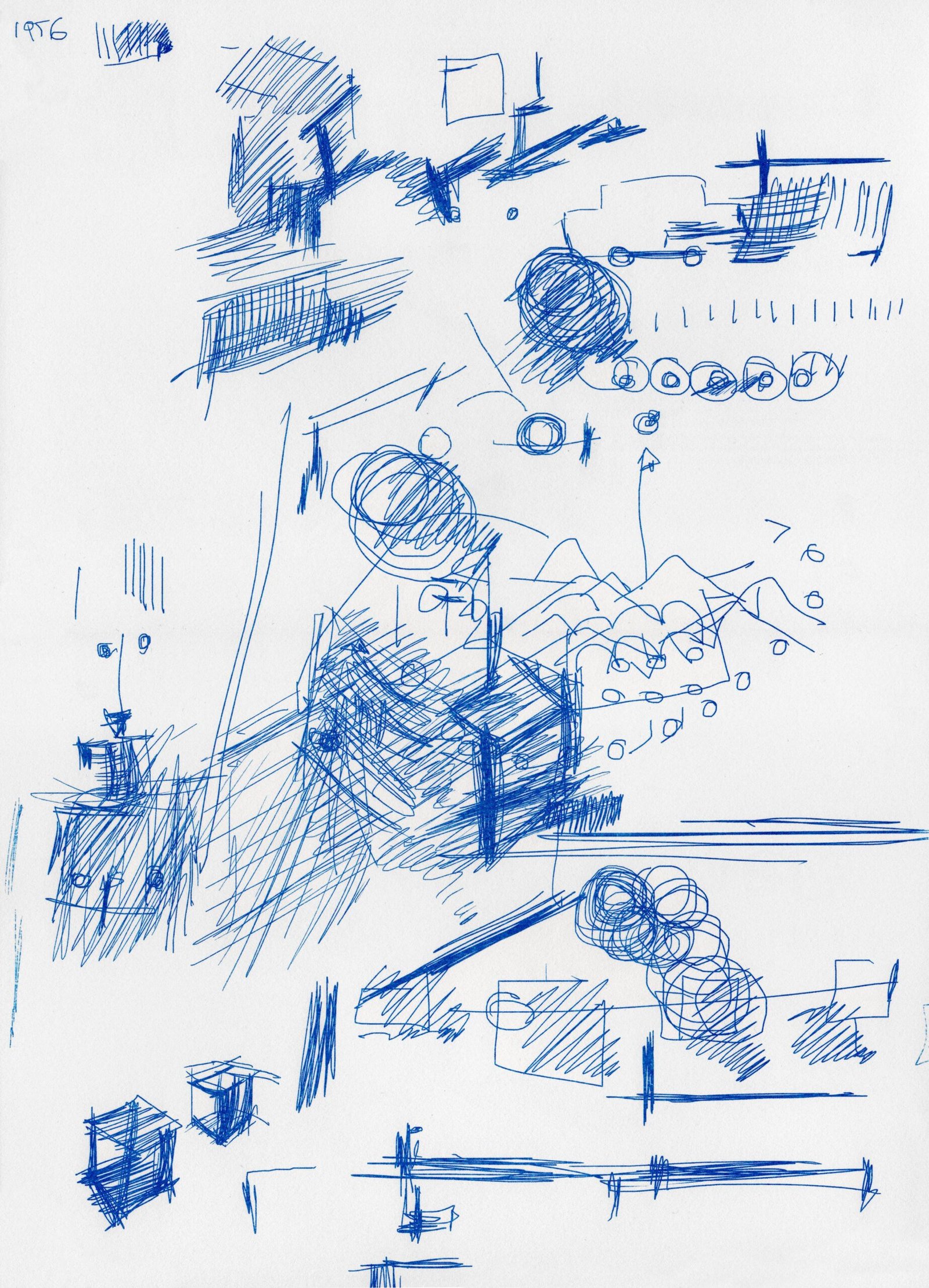

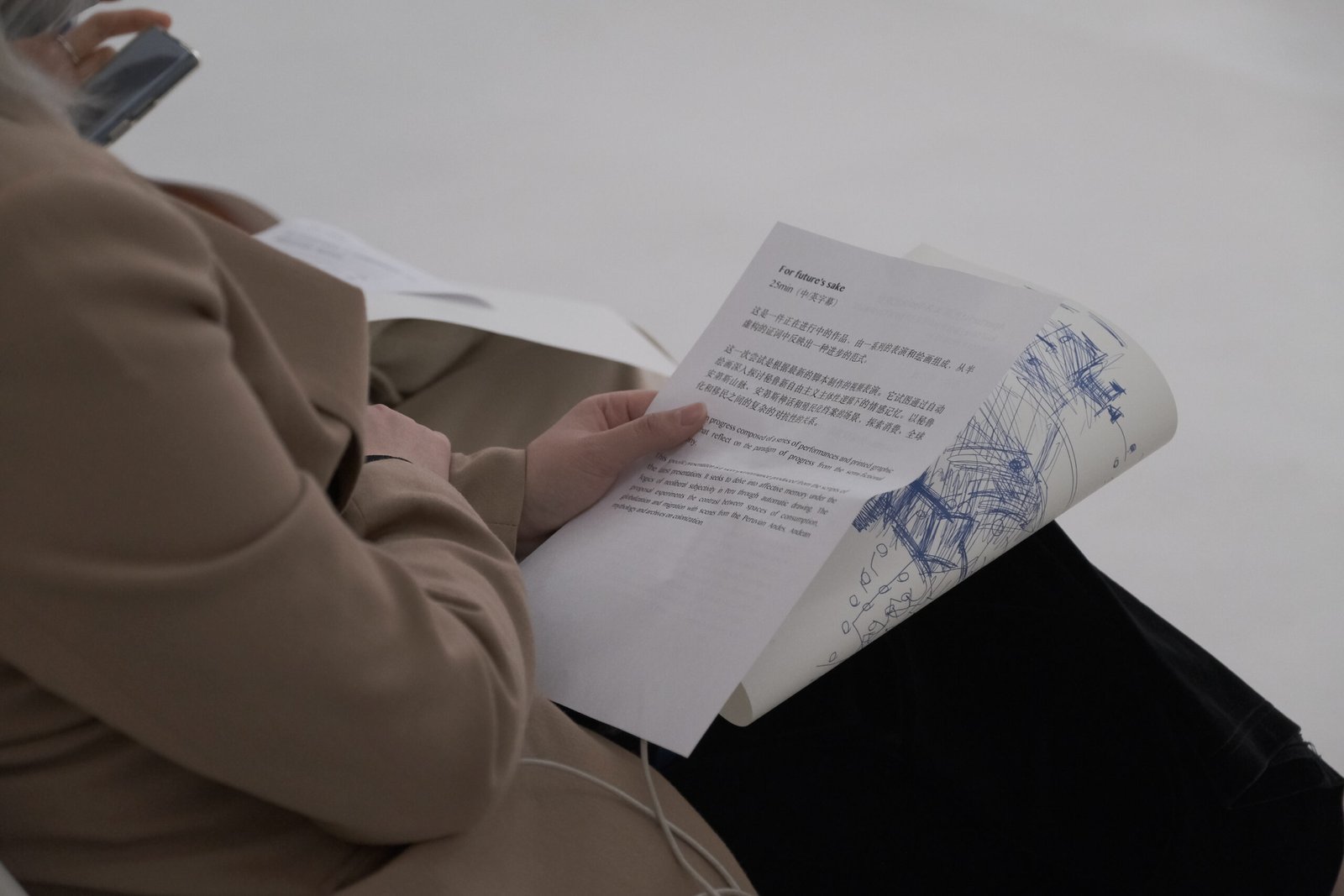

Fusion Machine is a project focused on the production of a series of video installations, lecture-performance, and a set of pictorial works that propose different approaches to the technical labor involved in the deployment and maintenance of telecommunications. The project is situated specifically in the context of Spain over the last century.

¿ADÓNDE IRÁ EL PÁJARO QUE NO VUELE? ¿ADÓNDE IRÉ YO QUE NO TE LLEVE?

LA CASA ENCENDIDA / LA PARCERÍA

The exhibition ¿Adónde irá el pájaro que vuele? ¿Adónde iré yo que no te lleve?, curated by Angel Calvo Ulloa and Julia Castelló, is accompanied by a parallel program taking place across various independent spaces in Madrid.

The project was presented at La Parcería. Over the course of five independent sessions, a performative reading was carried out, structured around three axes: the reading of a fictional testimony, the screening of a video, and the distribution of a publication. Developed from conversations with Spanish and Latin American technicians, the project proposes a connection between experiences of technical labor and the personal intersubjectivity tied to migration contexts and working conditions. The video also offers a contemplative view of manual and artisanal labor, highlighting the embodied knowledge and the systematization of gestures that make the continuity of the global network possible.

Acknowledgment:

VEGAP, Carolina Bustamante, Silvia Ramirez, Hector Vicente.

AIEP06.25

Photographic documentation of the lecture-performance Máquina fusionadora. Photo credits: Maru Serrano, La Casa Encendida.

Pages of the publication Máquina fusionadora, 2025

Photographic documentation of the lecture-performance Máquina fusionadora. Photo credits: Maru Serrano, La Casa Encendida.

Stills of Grace Hopper

MAPA COMÚN

CRISIS GALERÍA/BOMBON PROJECTS

Mapa común is the title of the inaugural exhibition of Crisis Galería/Bombon Projects in Madrid. Created together with Agnes Essonti Luque, “it traces a shared map that makes visible bodies, materials, and narratives that are usually excluded from the dominant visual field. In this gesture, they open a space to collectively reflect on the visible and invisible forms that sustain and condition our realities, proposing new cartographies from the sensorial and the political.»

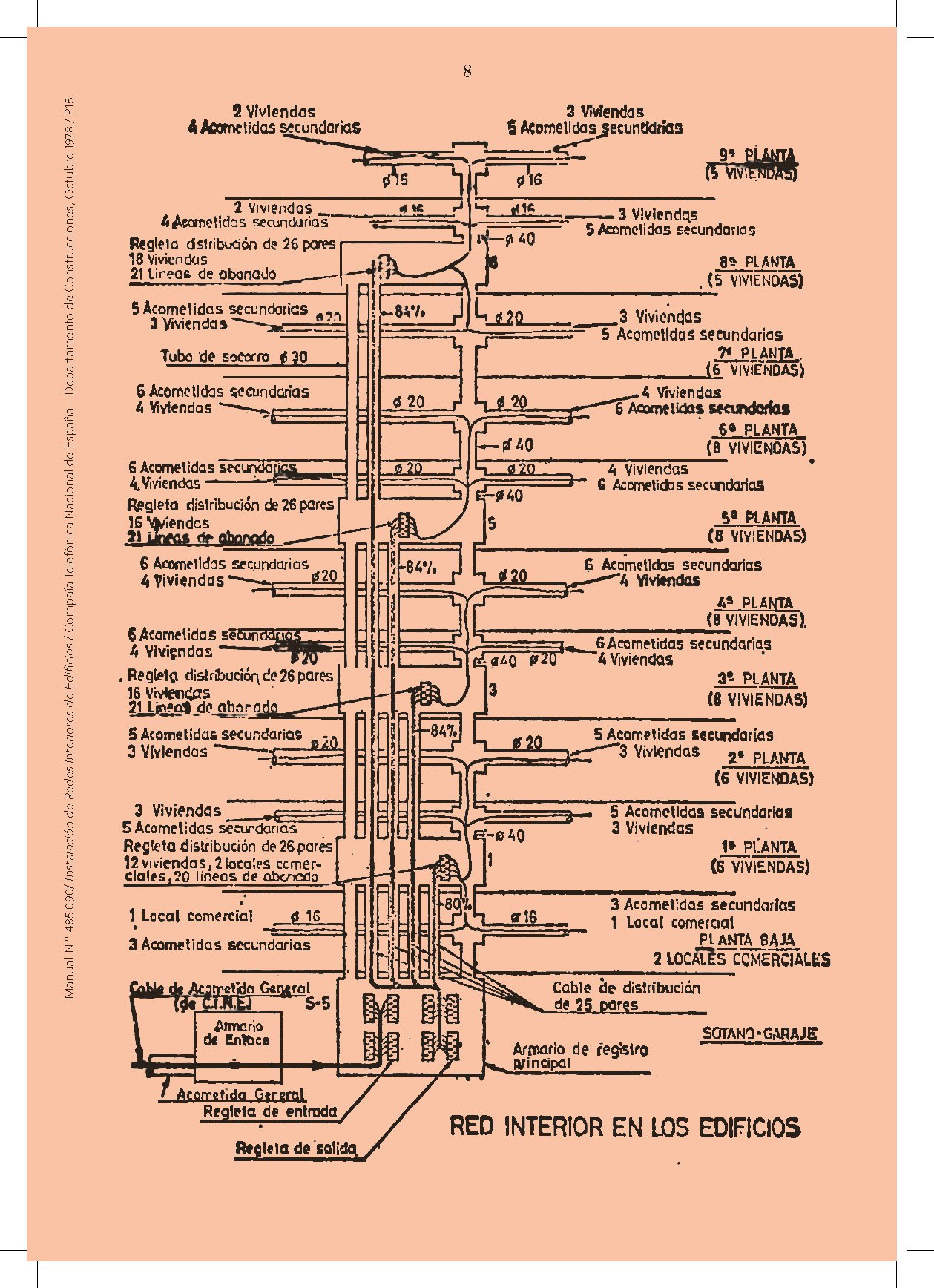

(…) “The works in this exhibition are primarily paintings, drawing on workers’ manuals, construction progress photographs, and graphic advertisements sourced from the archive of the Compañía Telefónica Nacional de España over the past century. This body of work engages with archival reproduction, approaching painting as a technical exercise of repetition. The selected images range from views of the subterranean foundations of Telefónica’s Gran Vía building to scenes of coaxial cable inspections carried out in public spaces. The exhibition also includes two graphic elements and a video. The floor-mounted posters reproduce drywall (pladur) advertisements, developed through research into printed publicity from various construction companies in the second half of the twentieth century. Alongside them is an illustration taken from an installation manual for concealed wall wiring. These two systems evoke almost contradictory conditions: the aseptic order of interior architecture set against the hidden technical infrastructure behind its surfaces.”*

*Fragments taken from the exhibition wall text.

Production process credits:

Fernando Dextre, Carmen Ojeda.

MC05.25

Exhibition views of Mapa Común. Photo credits: Roberto Ruiz.

Gateway 3

Oil on canvas

150x224 cm

2025

Cubiertas industriales

Oil on canvas

121x212.5 cm

2025

Gateway 4

Oil on canvas

130x291 cm

2025

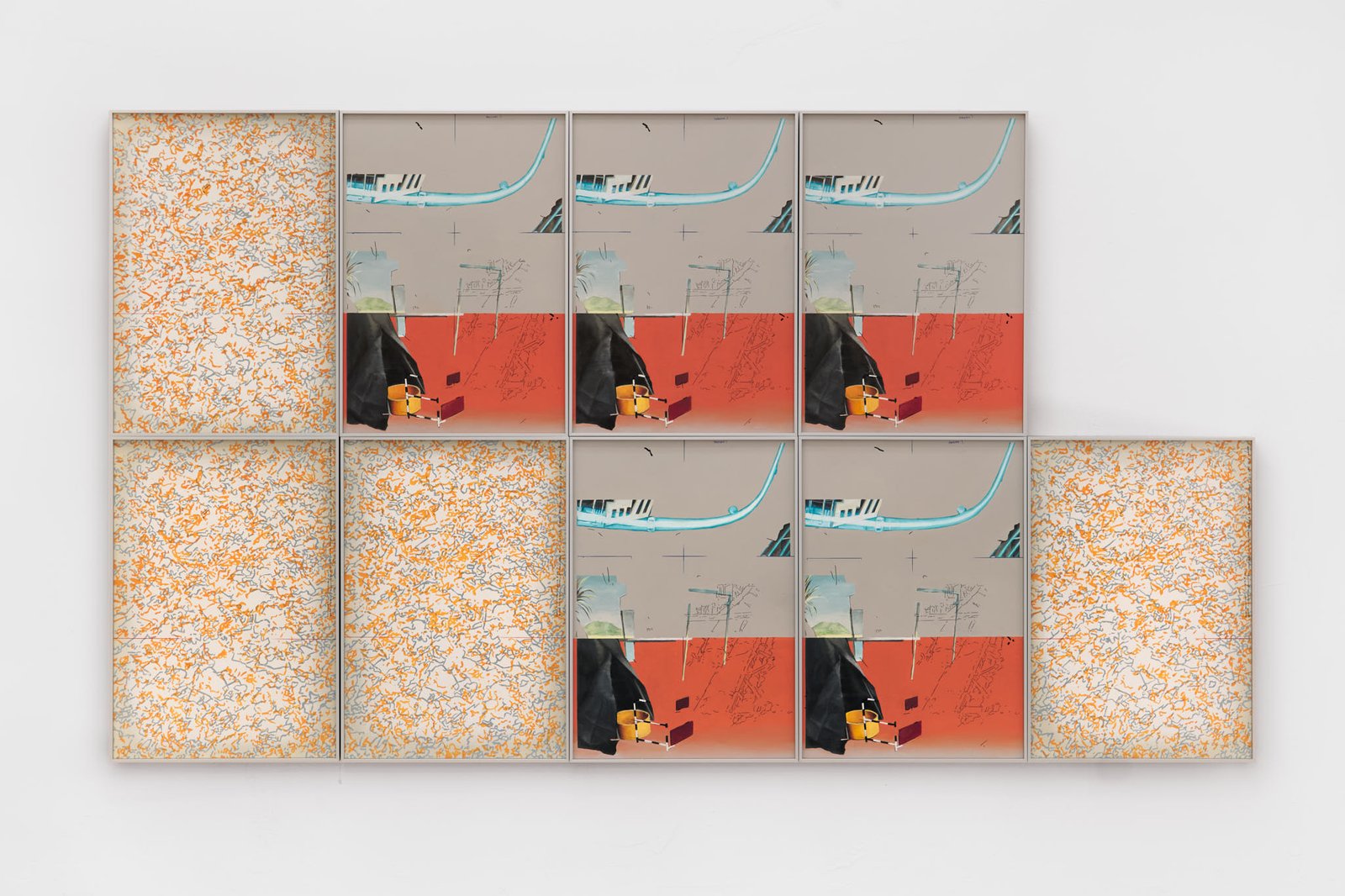

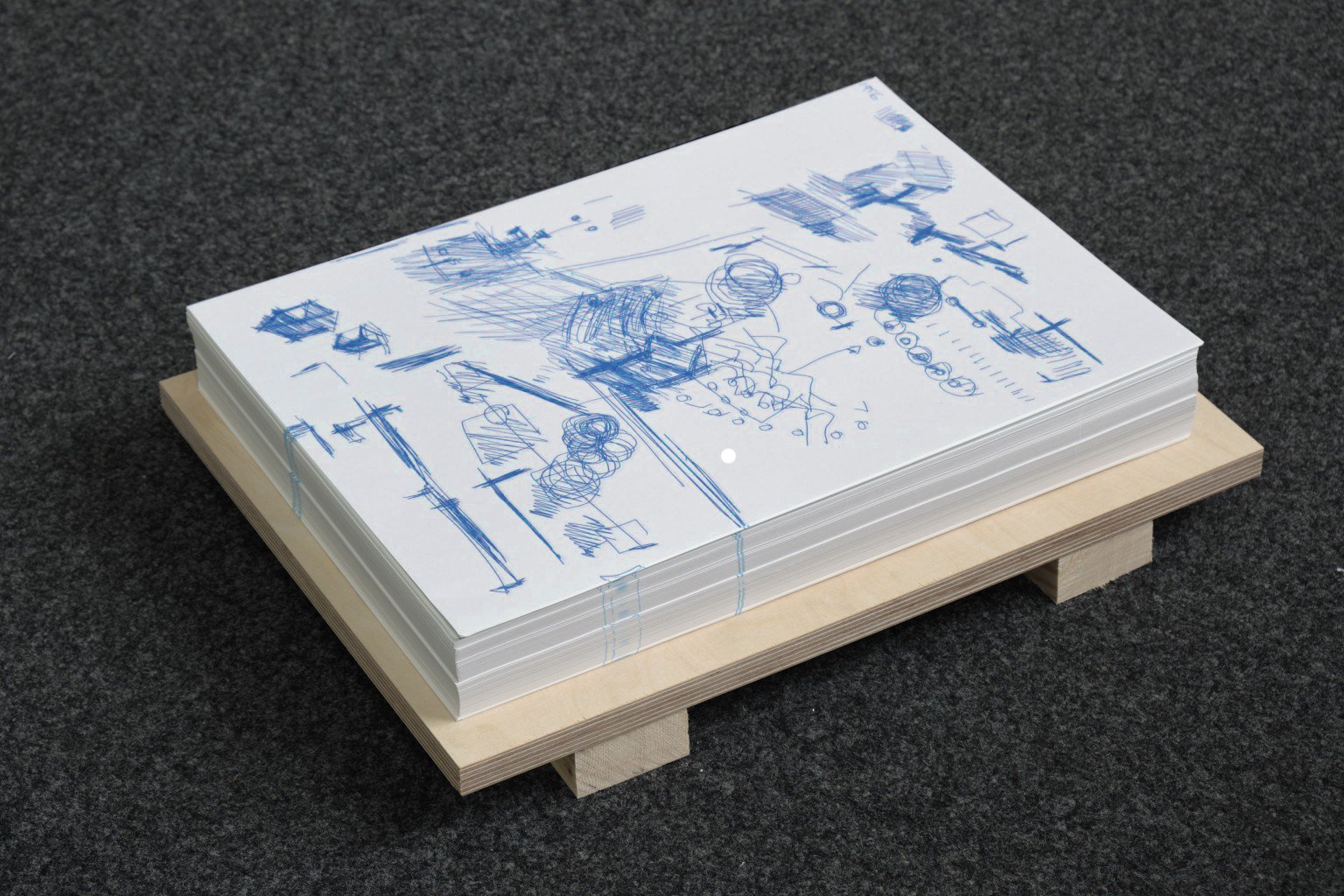

MÁQUINA FUSIONADORA

STAIN PROJECTS

«If the present we see and the future we imagine are regulated by the economic interests of the system, then speculating about the past can be a legitimate exercise for challenging the construction of the present. In recent months, I have been reviewing archives from telecommunications companies that have operated in Spain over the last century. From the telegraph to fiber optics, each communication system has been accompanied by its own specific advertising paradigm. From vestiges of the imperialist colonial expansion project of the nineteenth century to the late twentieth-century invocation of time acceleration, advertising has, effectively, directed our gaze and our desire towards globalization. This led me to ask: What would advertising have looked like if it had been true to the role of material infrastructure as the backbone of global interconnectivity?

To answer this question, I set out to create three different advertising posters, drawing from the aesthetics and content of communication archives that circulated in Spain up until the second half of the nineteenth century. I produced three sketches, which I manually intervened until arriving at a somewhat more concrete idea, later finalized in digital format. What you see in the exhibition space are the three preliminary sketches, each of which has been manually reproduced four additional times.

Hand reproduction may seem like an almost obsolete gesture—less rational and more operative. You quickly realize that the work must be systematized in order to reduce the time it takes. At times it was tedious, but it gathered momentum as I reached the satisfaction of standing before multiple repetitions. It becomes inevitable to think that the unique object suddenly divides its value into multiple identical ones, and to recognize that the value of the aesthetic and the artistic—often attributed to immaterial or even mystical forces—can, in fact, be copied, because in the end it is a physical material, a tangible presence laid upon a surface.

*Fragments taken from the exhibition wall text.

Production process credits:

Adela Angulo Portugal, Carmen Ojeda, Tabata Pardo.

MF03.25

Exhibition views of Máquina Fusionadora. Photo credits: Juan David Cortes, Stain

Cuando el tiempo lo es todo

Oil on paper

60x42 cm

2025

La energía del mundo

Oil on paper

60x42 cm

2025

Los satélites por el prestigio

Oil on paper

60x42 cm

2025

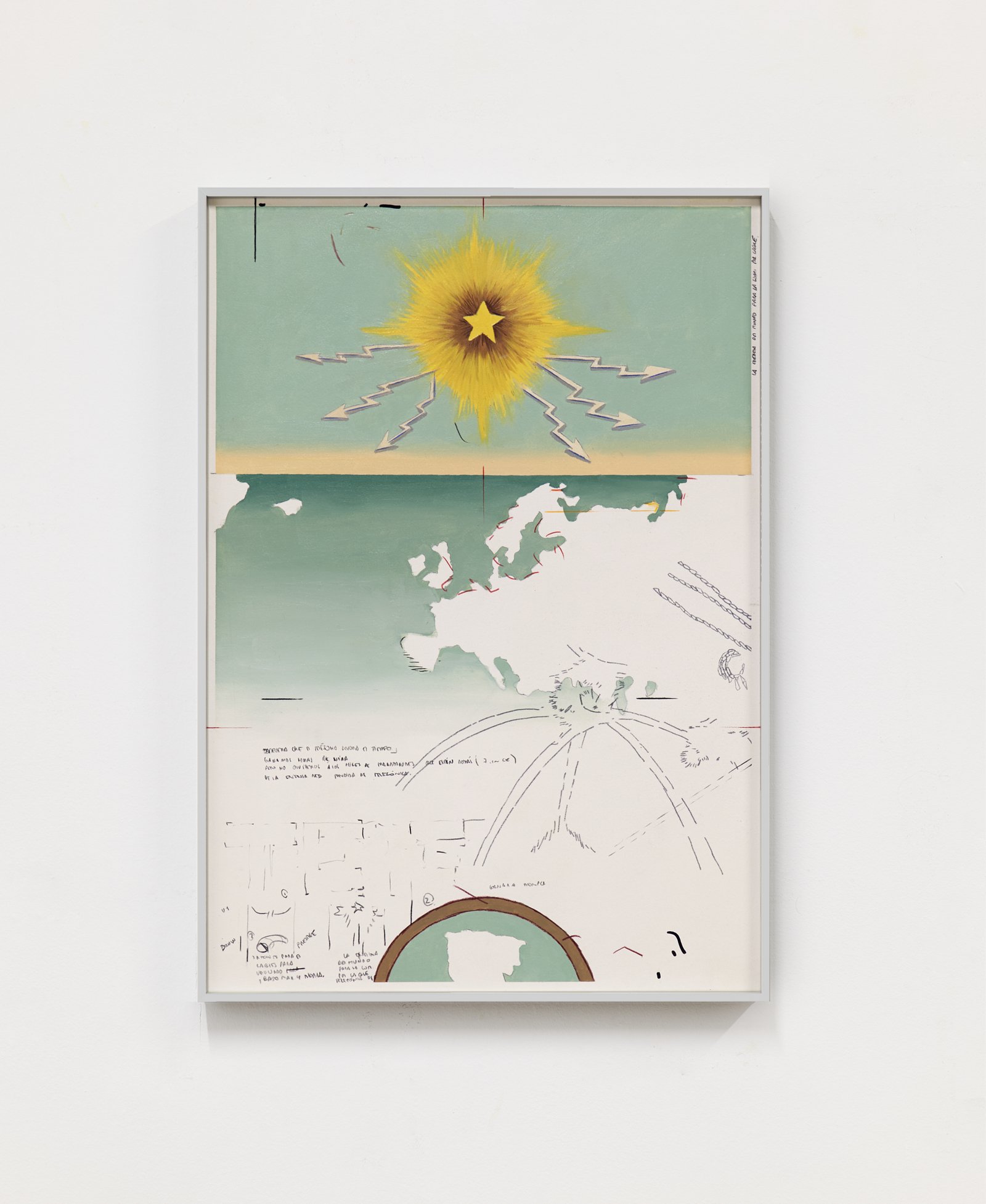

RAYOS DE SOL DE SUDAMÉRICA

(RAYS OF SUNLIGHT FROM SOUTH AMERICA) BS07.25 / MP05.25 / EBALC02.25 / CTLMATR02.24 / RDSDS09.23

RAYOS DE SOL DE SUDAMÉRICA

(RAYS OF SUNLIGHT FROM SOUTH AMERICA) BS07.25 / MP05.25 / EBALC02.25 / CTLMATR02.24 / RDSDS09.23

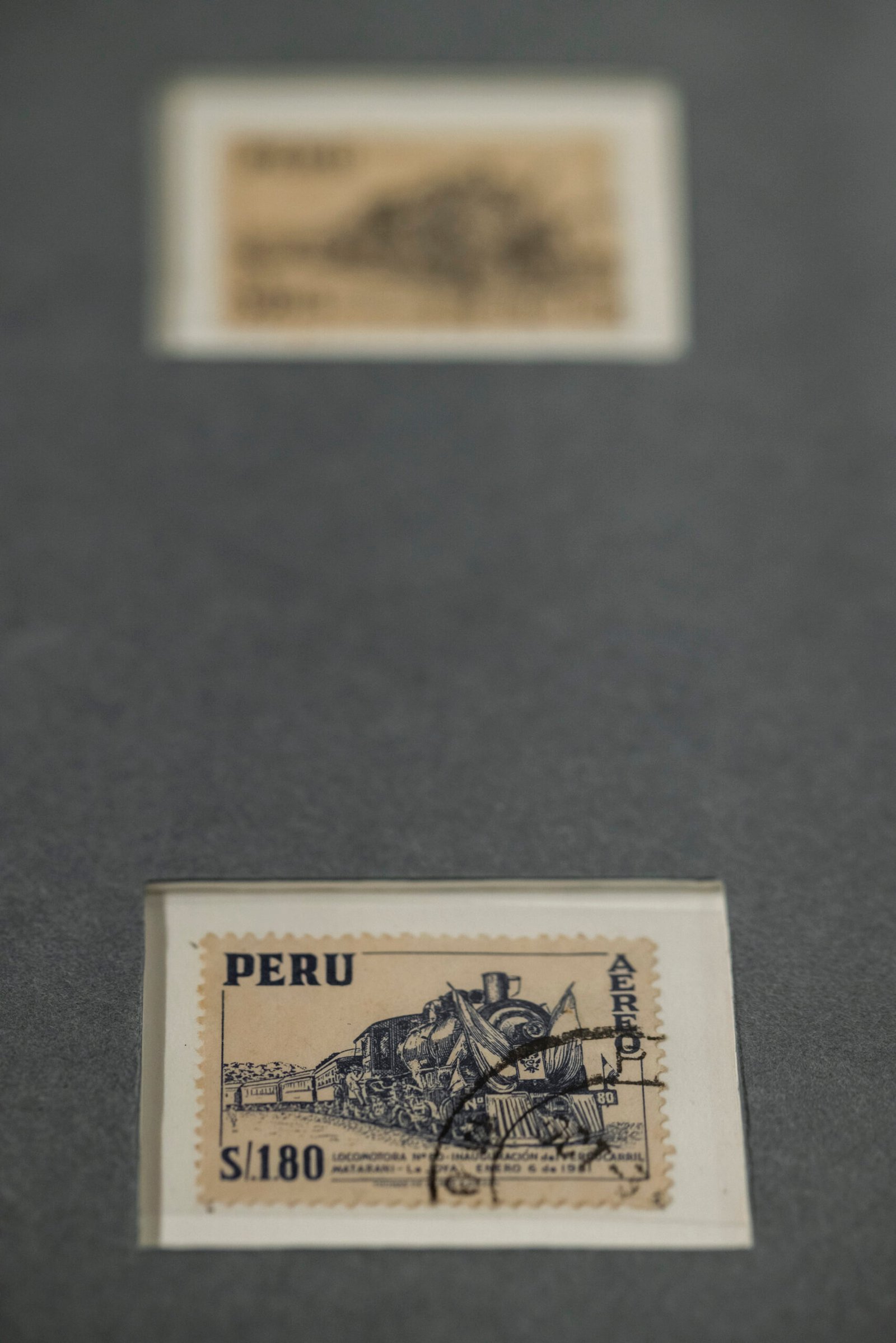

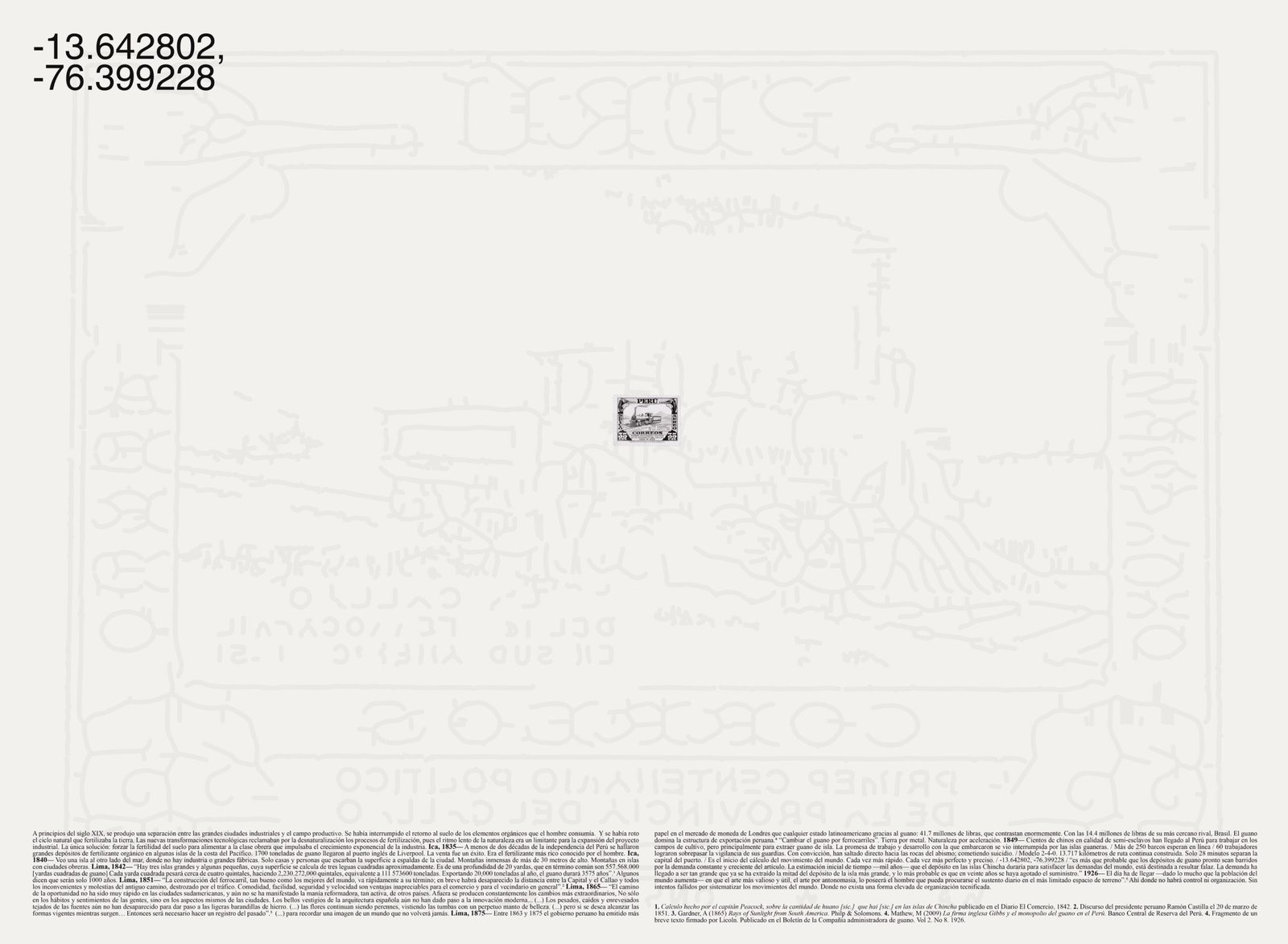

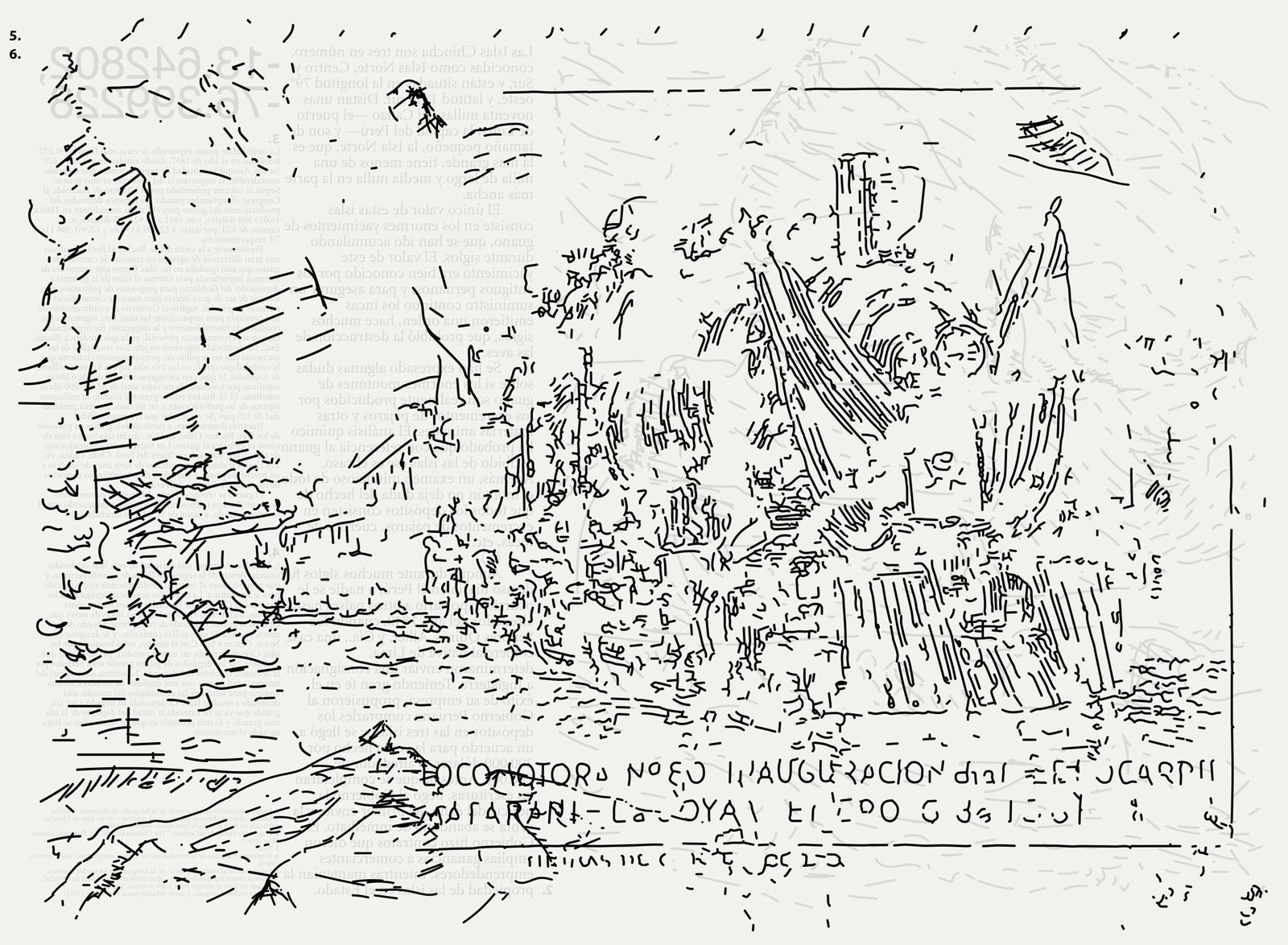

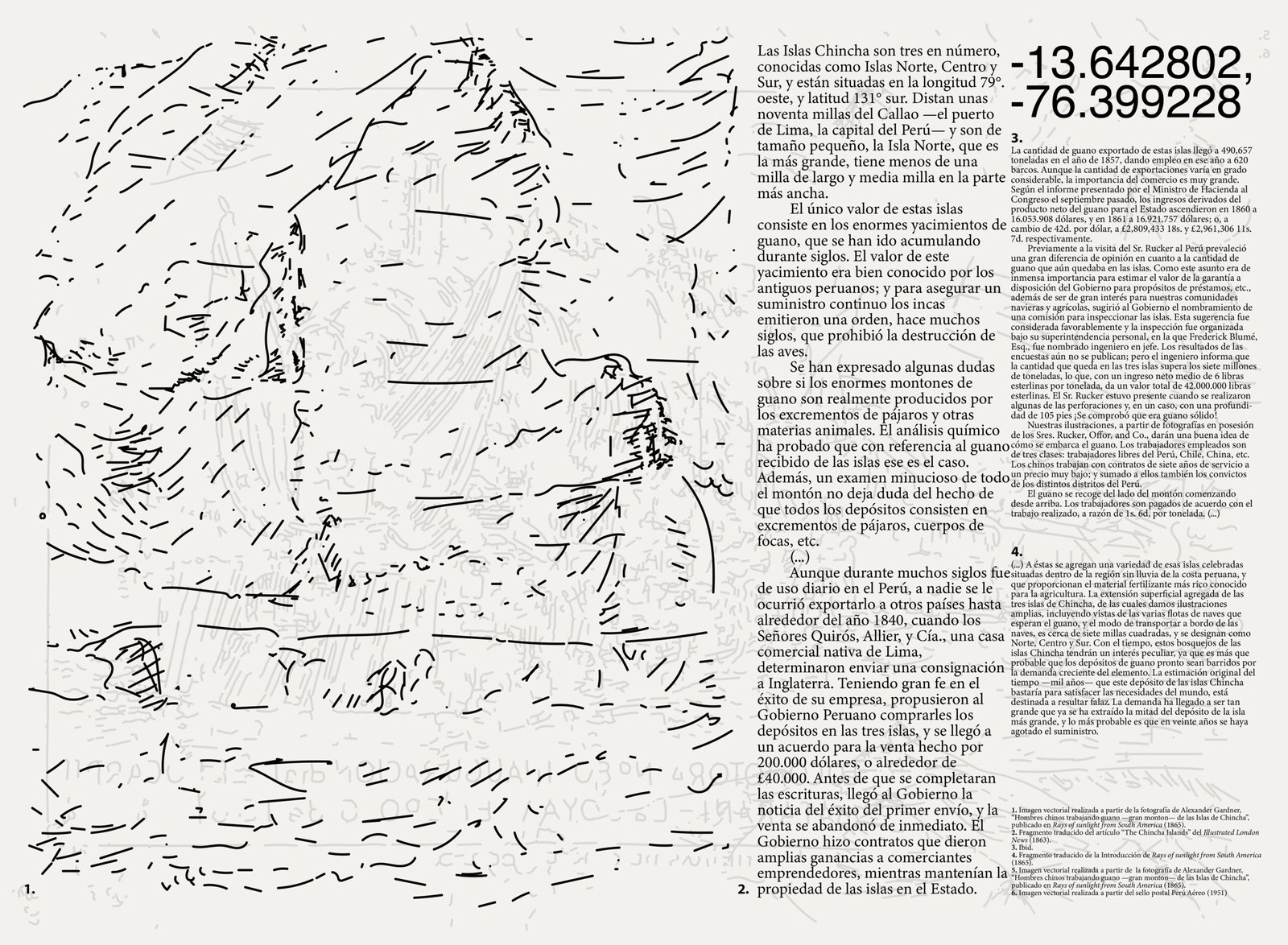

In 1851, Peru financed the construction of the first passenger and cargo railway line in South America, linking Lima, the capital, to the port of Callao. A symbol of development and national identity, the project marked the beginning of the construction of an extensive network of railway connections that would streamline and expand the market inside and outside the country in the following years. The economic system was transitioning to a capitalist model and the country had become aligned with a vision of progress and modernisation, using as collateral a somewhat unusual element: vast mountains of fertiliser produced by birds that had accumulated on the islands of the Pacific coast. Known as “guano”, this element had attracted the interest of the industrial powers that were battling with a problem of soil fertility due, on the one hand, to the separation of the big cities and the countryside and, on the other, to the growth of the working-class population. This gave Peru the liquidity it needed to access loans, which would subsequently attract new investors and consolidate new negotiations with industrial countries, using its own natural resources as its currency.

This seminal historical period, which connected Peru to the world, was marked by trading processes that were mediated by slow technologies, as it took two and a half months by boat to connect the port of Callao to the port of Liverpool in England. Commodities, letters and photographs were transported to distant destinations and became part of an increasingly complex global fabric. Today, nearly 170 years later, fibre optics and satellite networks transport information across the Atlantic Ocean at a speed of nearly 200,000 kilometres per second.

This enormous contrast explains the acceleration of trade Catch the living manners as they rise at a global level. But not only that: it also explains why production and distribution processes have become invisible. Today, the visible face of these transactional processes—digital communication networks—seems to have acquired an immaterial pure form, driven by the coordination of computer vectors that can be used to produce graphical vectors. These are perfectly drawn lines of coordinates that can be extended infinitely. Today, they are used to design all digital interfaces. The principles of the vector are apparently perfect for representing the logic of infinite growth demanded by the age of progress and the market in the current system. Thus, while the ideal form of capital is managed through the concepts of infinite progress and consumerism, its material form is sustained by the finite nature of the planet.

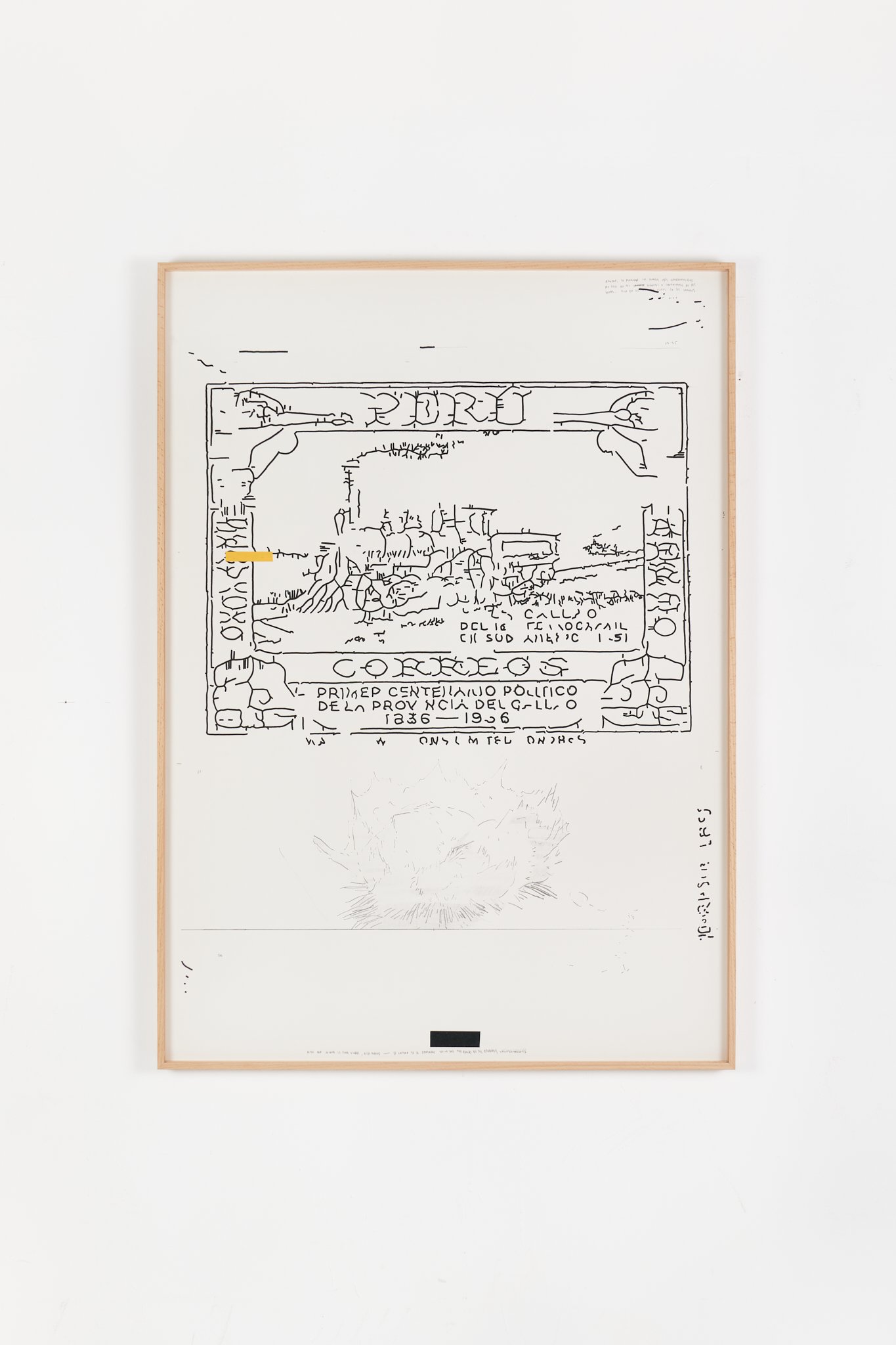

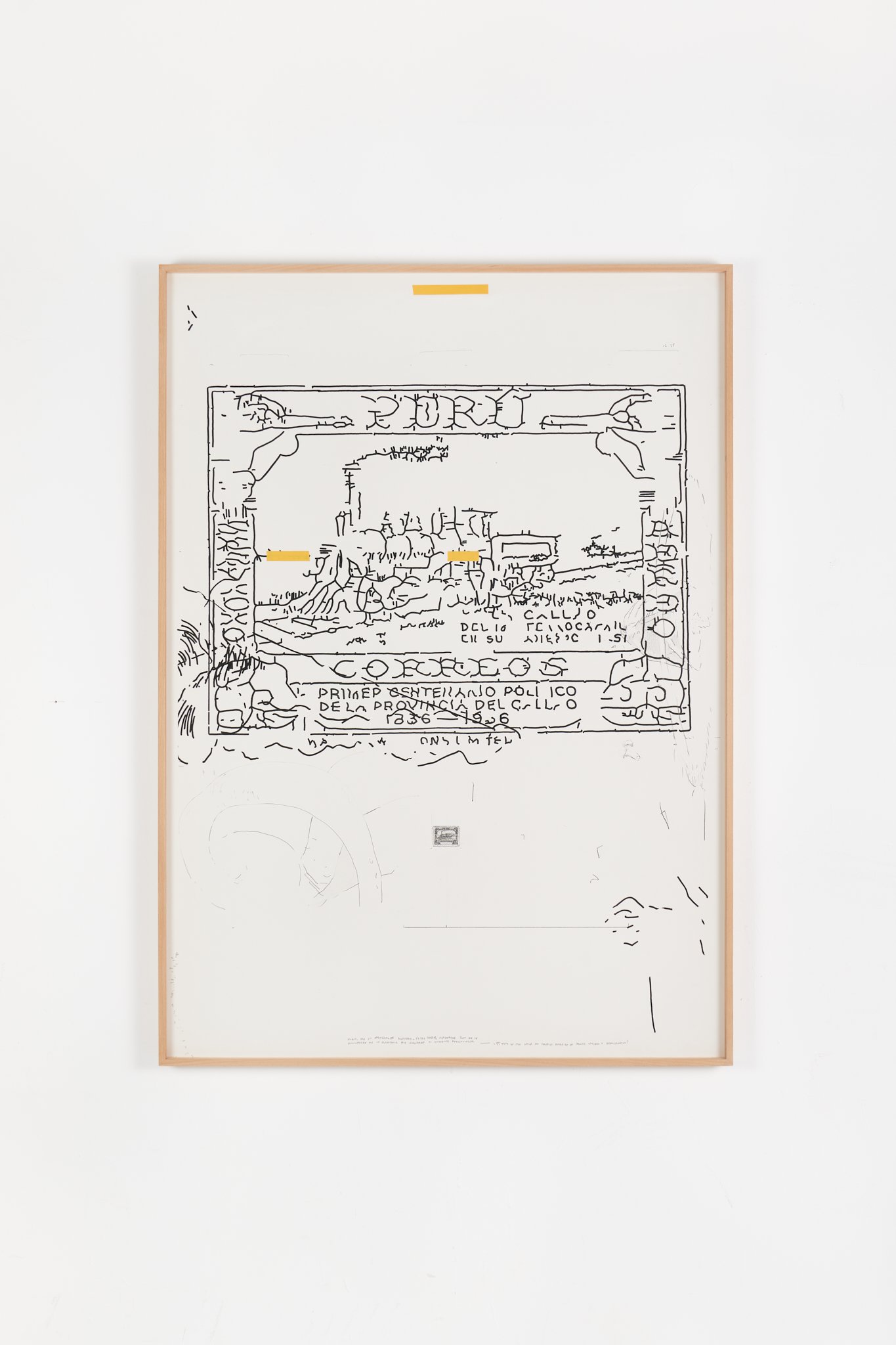

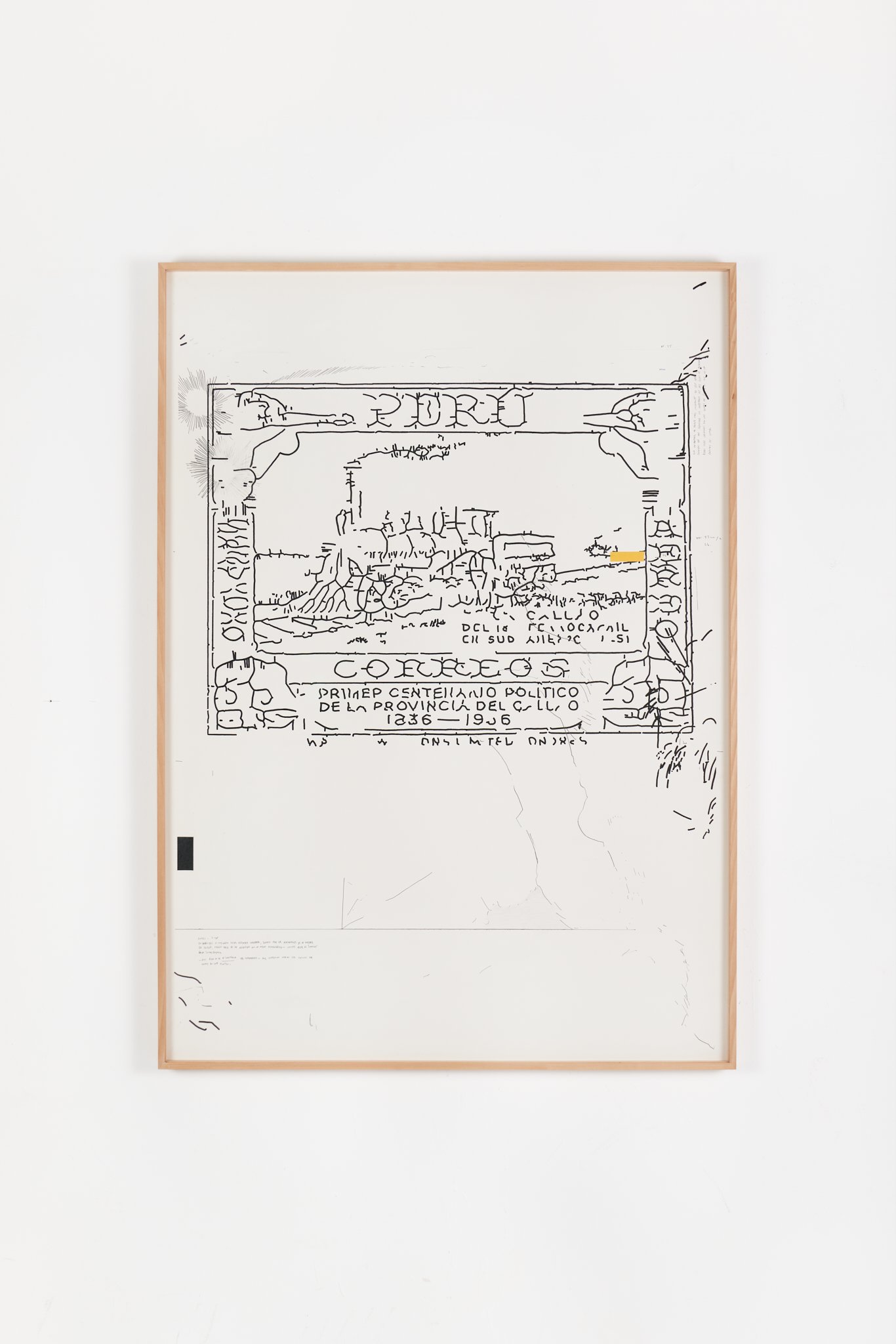

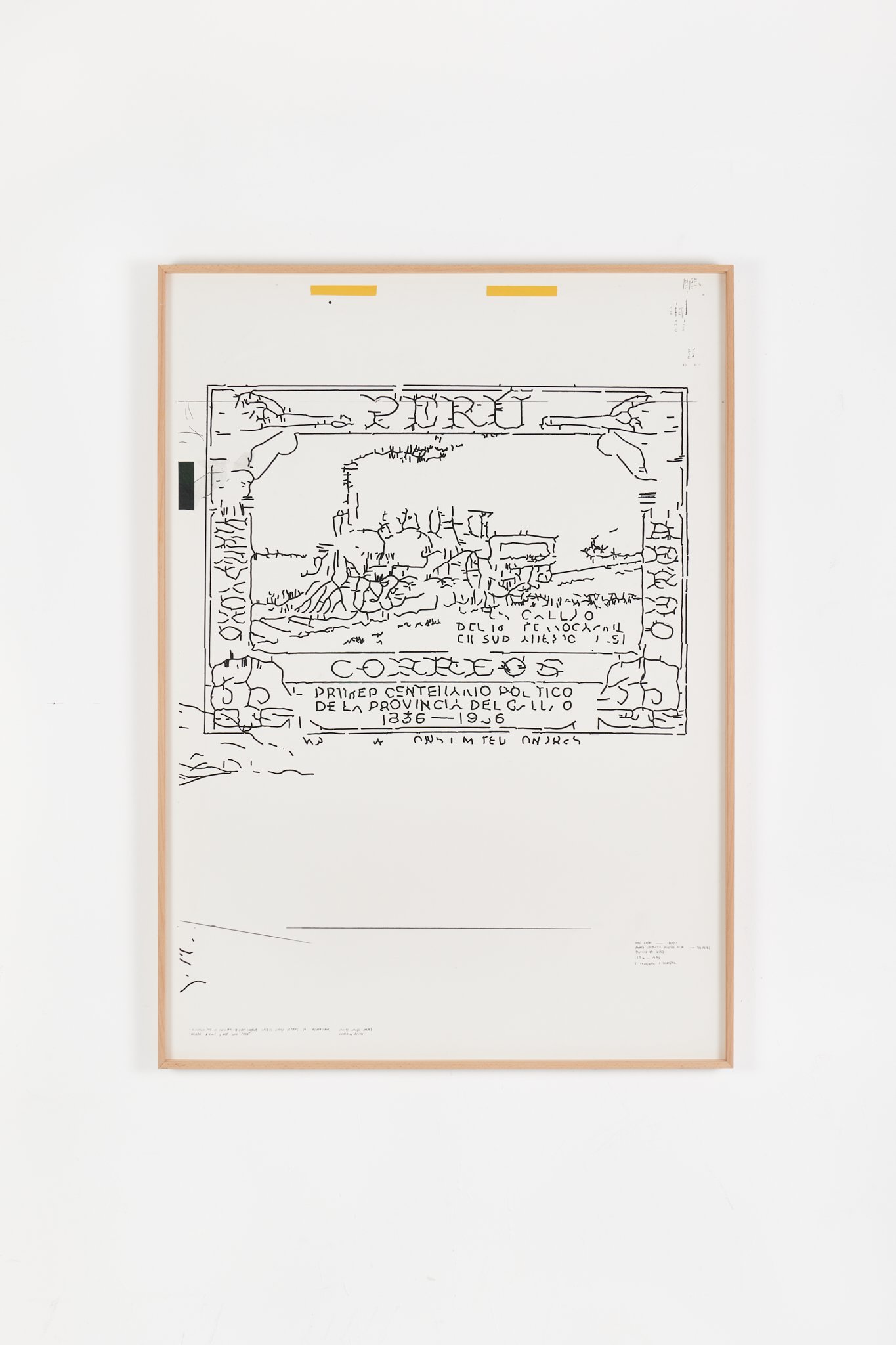

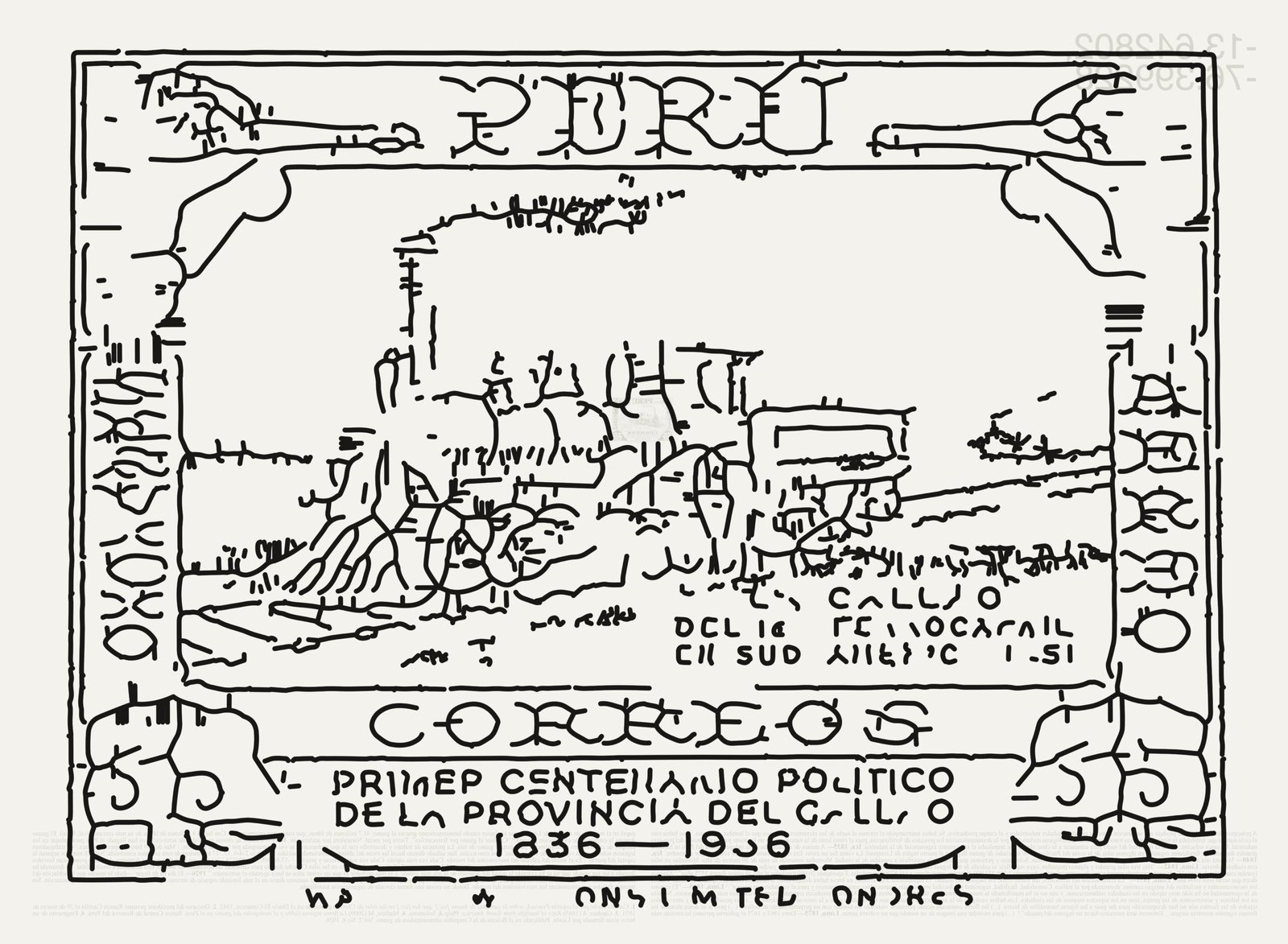

Graphical vectors seem to have become the ideal medium for disseminating a universal mandate of the visuality of the globalised world, with corporate images, the graphical identity of major franchises and the construction of commercial networks all at our fingertips and all drawn from the outline of a perfect synthesised graphical form. Meanwhile, behind all this, exploitation and inequality uphold that same economic model through transnational under-development. To extract guano in the mid-nineteenth century, nearly six hundred coolies arrived from China in the capacity of semi-slaves, and the guano quarries that promised prosperity and constant extraction for more than a thousand years dried up in less than sixty. A postage stamp commemorating the centenary of Peru’s first port illustrates this apparently contradictory relationship between nature and technology. It shows a railway line decorated on both sides with guano birds

Rayos de sol de Sudamérica proposes a revision and digitalization of the historical archives of the extraction of guano from the Chincha Islands and its vectorization for the elaboration of a series of performative and material activations. The center of these interventions is the production of a series of macro videos of the printed vectors. The camera advances zenithally following the lines to simulate the advance of a railway line. The proposal seeks to pose an opposition between the digital and the materiality within the extractive imaginary of guano. The graphic vector as an ideal model breaks down the moment it materializes in a printed form, since its possibility of infinite enlargement is annulled when it is opposed to the material reality.

EXTRACTIVISMS. 13TH LEANDRE CRISTÒFOL ART BIENNALE

CENTRE D’ART LA PANERA

Group exhibition curated by María Íñigo Clavo and Christian Alonso. «The 13th Art Biennale Leandre Cristòfol focuses on the processes of resource extraction: on its implications, its contestations and its alternatives. With a prominent presence of Latin American artists, the exhibition responds to ecosocial crises with works that offer an antidote to the utilitarian vision of nature. The projects alert us to the consequences of a development based on intensive extraction and the commodification of resources in the service of unlimited growth and excessive consumption. Based on situated, critical and affirmative methodologies, the works situate life at the centre of ethical, political and economic issues; they reconsider the ways of valorising human and non-human life, and promote practices based on the common well-being.

Extractivism is a mode of production based on the privatization, extraction and commercialization of natural resources. This dynamic originates in European colonization, and in the exploitation of goods, bodies and knowledge this process entails. Today, extractivism is the operating logic of neoliberal capitalism, and is practiced by companies and governments everywhere. The argument that legitimizes extractivism is that it generates jobs and contributes to economic growth. However, it has profound impacts on people and ecosystems: it generates social inequalities and territorial conflicts; it contributes to resource depletion, biodiversity loss and environmental pollution; it produces large amounts of waste, and it strips local communities of their resources and territories.

The projects included in the Biennial demonstrate that contemporary extractivism is not only feeds on natural resources, but also by social, cultural and digital resources. Focusing on Spain’s colonial history with North Africa and Latin America, the works highlight the link between extractivism, colonialism and environmental degradation; they warn us of the pitfalls of green marketing; they speak of the extractive function of mass tourism, urban gentrification and information and communication technologies; they question the biopolitical function of landscape painting and the sculptural monument; they speak of the capacity for resistance of local communities; they show the restorative function of ancestral rituals based on respect and interdependence with nature; they carry out healing actions from popular culture, spirituality and the feminization of struggles.»*

*Fragment taken from the curatorial text.

Production process credits:

Carmen Ojeda.

EBALC02.25

Exhibition views of Extractivisms. 13th Leandre Cristòfol Art Biennale. 2025.

Untitled 1-6 (from the series Rayos de sol de Sudamérica)

Graphite and ink on paper

120x86 cm

2025

Detail views of Extractivisms. 13th Leandre Cristòfol Art Biennale. 2025.

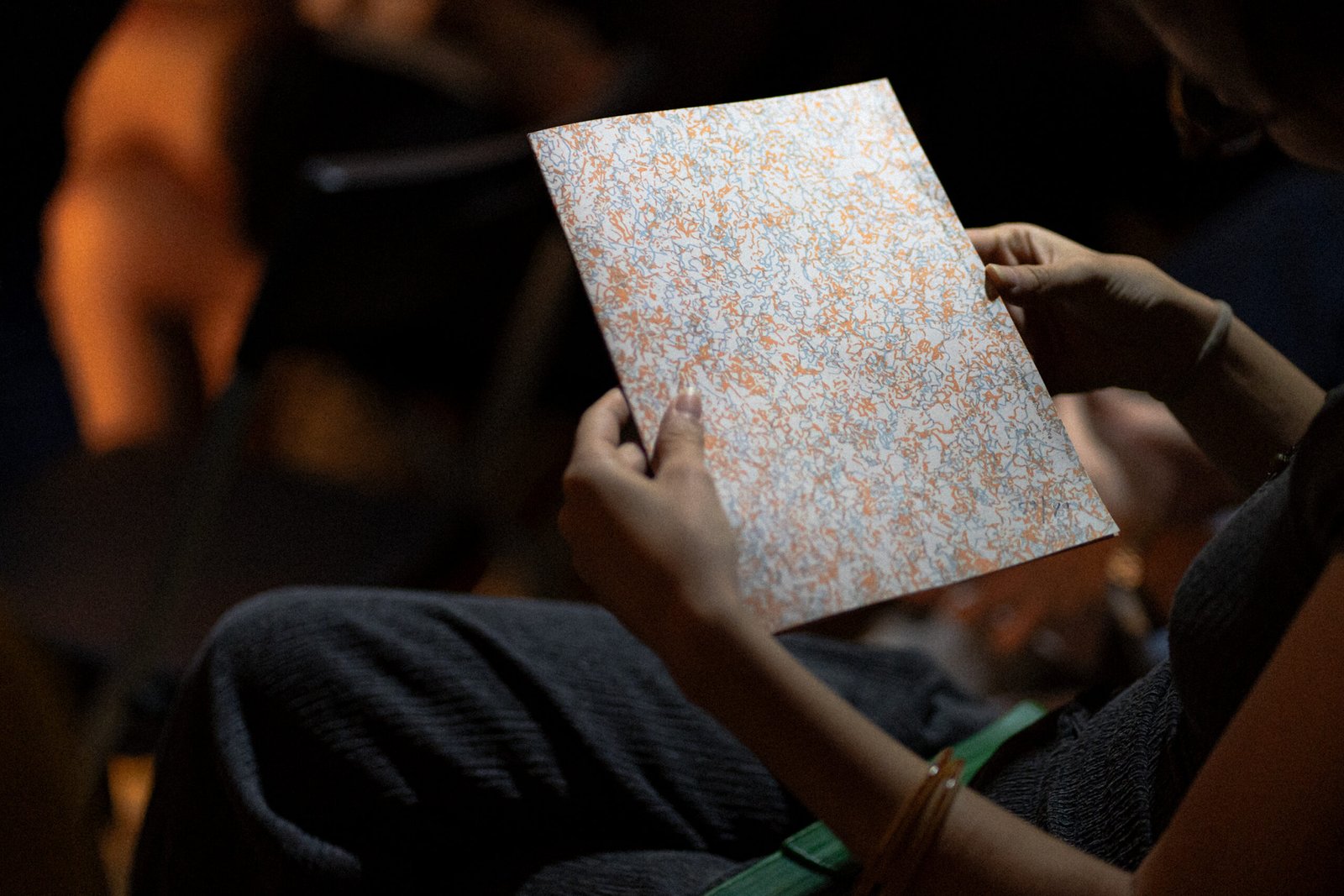

CATCH THE LIVING MANNERS AS THEY RISE

LA CASA ENCENDIDA

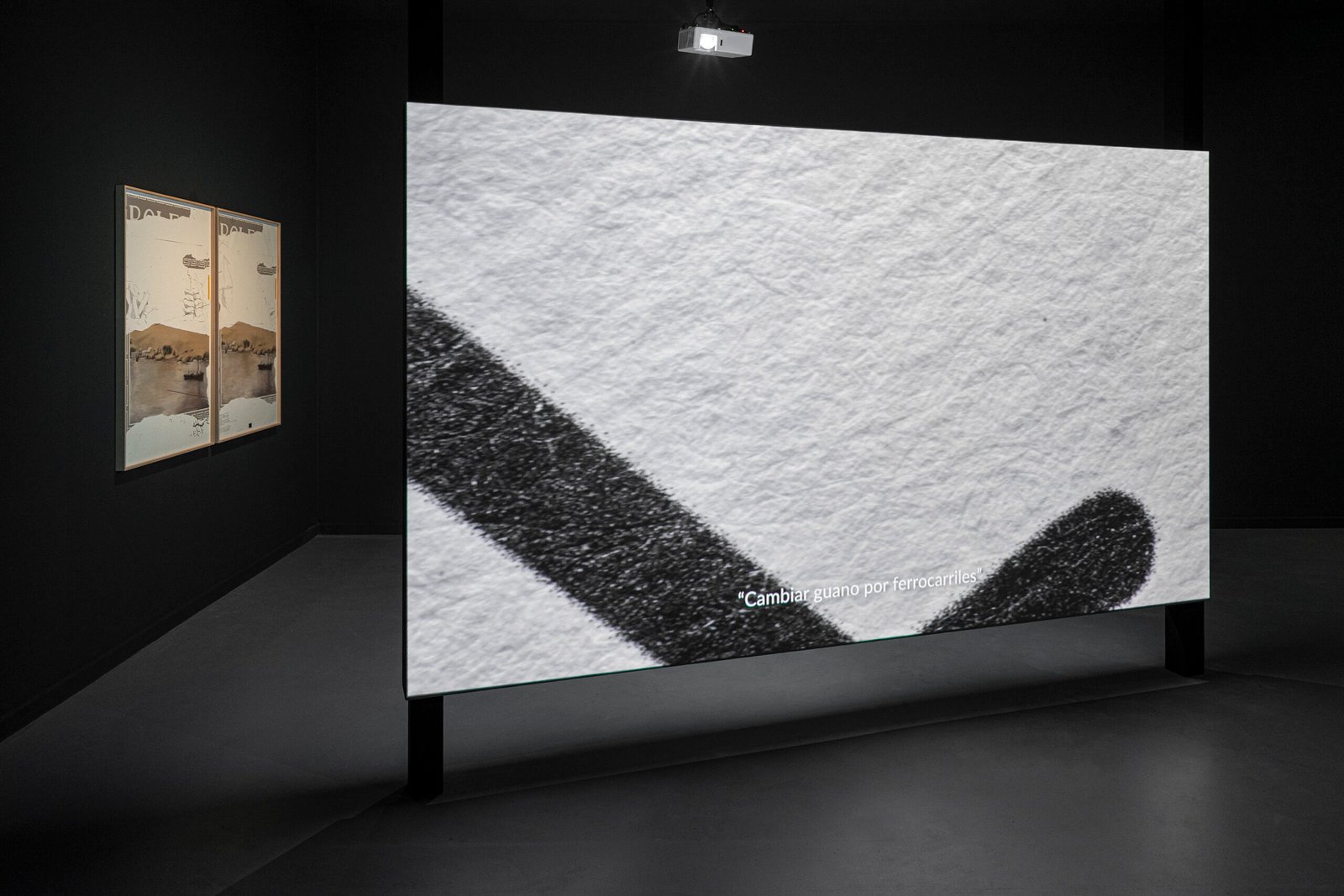

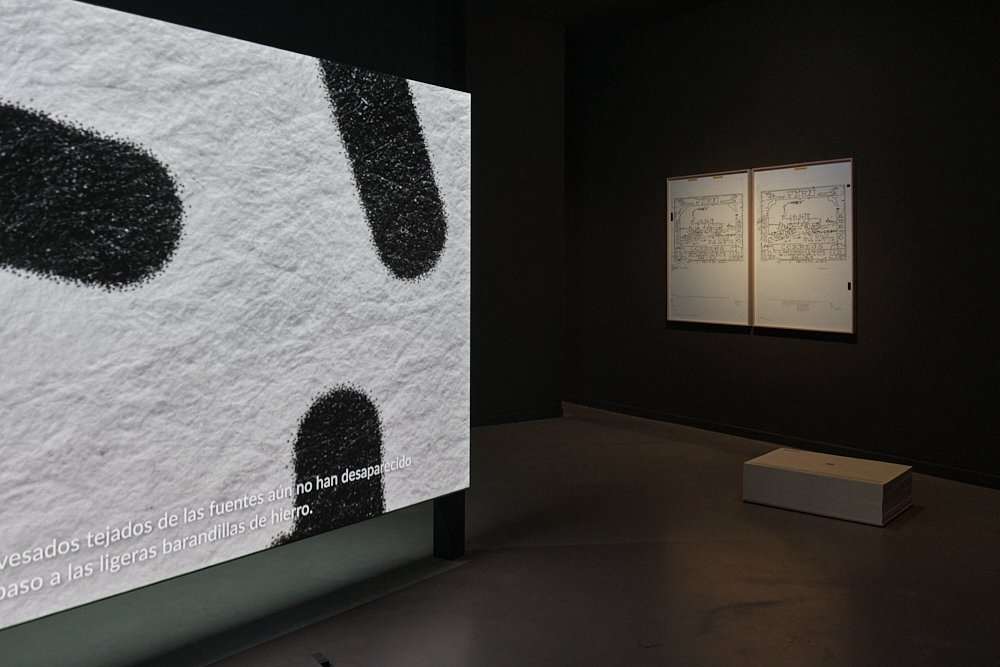

Presented as part of Generación 2024 at La Casa Encendida, the two-channel video Catch the Living Manners as They Rise is shown.

«Graphical vectors seem to have become the ideal medium for disseminating a universal mandate of the visuality of the globalised world, with corporate images, the graphical identity of major franchises and the construction of commercial networks all at our fingertips and all drawn from the outline of a perfect synthesised graphical form. Meanwhile, behind all this, exploitation and inequality uphold that same economic model through transnational under-development. To extract guano in the mid-nineteenth century, nearly six hundred coolies arrived from China in the capacity of semi-slaves, and the guano quarries that promised prosperity and constant extraction for more than a thousand years dried up in less than sixty. A postage stamp commemorating the centenary of Peru’s first port illustrates this apparently contradictory relationship between nature and technology. It shows a railway line decorated on both sides with guano birds. Catch the living manners as they rise consists of the vectorization of this postage stamp to make a dual-channel video. The first video reproduces a macro tour of the vectorized digital image, while the second one makes the exact same tour but this time printed on paper. The proposal aims to present an opposition between the digital and the material with the extractive imagery of guano. The notion of the graphical vector as the ideal model collapses when it is materialized in printed form, as the possibility of infinite extension vanishes in contact with the material reality.»*

*Fragments taken from the curatorial text.

Acknowledgments:

Centro de Residencias Artísticas de Matadero, Andrea Muniain

CTLMATR

Exhibition views of Generación 2024. Photo credits: Maru Serrano, La Casa Encendida 2024.

Catch The Living Manners as They Rise (front)

Offset print

55x75 cm

2024

Catch The Living Manners as They Rise (back)

Offset print

55x75 cm

2024

Stills from the video Catch The Living Manners as They Rise

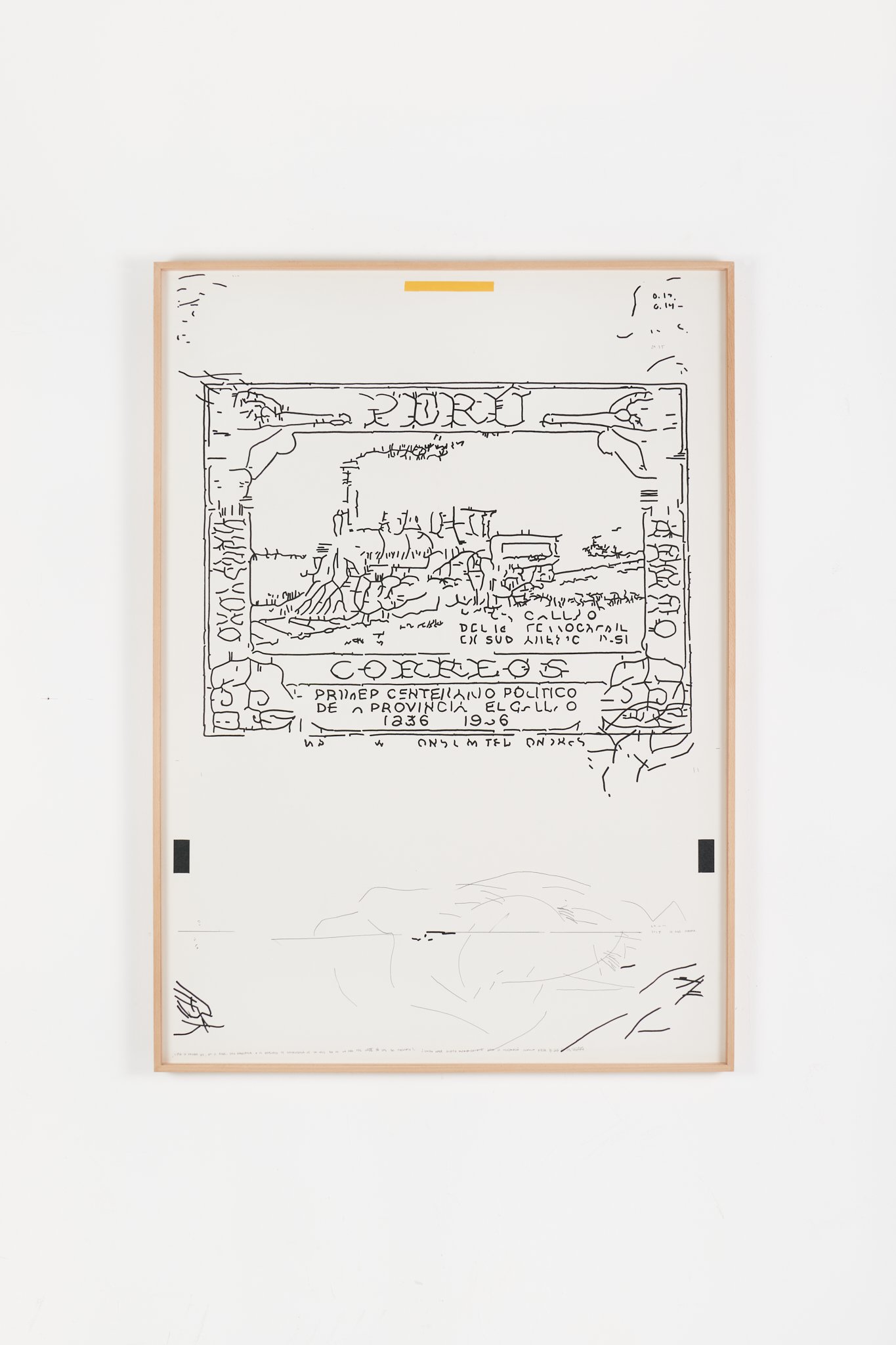

RAYOS DE SOL DE SUDAMÉRICA

CRISIS GALERÍA

In 1865, photographer Alexander Gardner published the photo album Rays of Sunlight from South America, a selection of photographs of Peru taken by American photographer Henry De Witt Moulton around 1863. This album features images of the city of Lima and the Chincha Islands, known for their large guano deposits. One photograph stands out: a giant mountain of substrate, nearly 30 meters high, imposing in contrast with the diminished workers, semi-slaves digging into the already fossilized surface under the sun. The overall selection highlights the contrast between civilization and nature, and between culture and resource extraction.

Since I first saw this album, I have wondered why it was given that name: “Rays of Sunlight from South America.” The most obvious answer seems linked to the new technological medium that produced it —other albums from that era also had titles referencing light or the sun as a way to evoke the genesis of the photographic image— but I can’t stop thinking that there is a deeper connection, perhaps related to the idea of hope and progress. It is as if Gardner wanted to point to the existence of a ray of light as an ideal of progress emerging from the shadow of a young Peru, independent for only four decades; and still seemingly unready to embrace the industrial transformations that were accelerating the world.

This project is divided into two rooms and is based on that strange relationship contained in the guano context: local nature–global industry, interconnectivity, and progress; all situated in a key historical moment—the second English industrial revolution and the beginning of Peru’s slow transition into the capitalist economic system.

Acknowledgment:

Centro de Residencias Artísticas de Matadero, La Casa Encendida, Centro Huarte, Imaginary Z.

RDSDS09.23

Exhibition views of Rayos de sol de Sudamérica. Photo credits: Juan Pablo Murrugarra.

VOL 26-1950

Oil and graphite on paper

100x70 cm

2023

VOL 5-1929

Oil and graphite on paper

29.7x42 cm

2023

Islas de chincha(front)

Offset print

29.7x42 cm

2023

Islas de chincha (back)

Offset print

29.7x42 cm

2023

Artworks displayed in the exhibition Rayos de sol de Sudamérica

Still of the video Islas de chincha

IMAGEN DÉBIL, CICLO PERMANENTE

(WEAK IMAGE, PERMANENT CYCLE) LAF06.22

IMAGEN DÉBIL, CICLO PERMANENTE

(WEAK IMAGE, PERMANENT CYCLE) LAF06.22

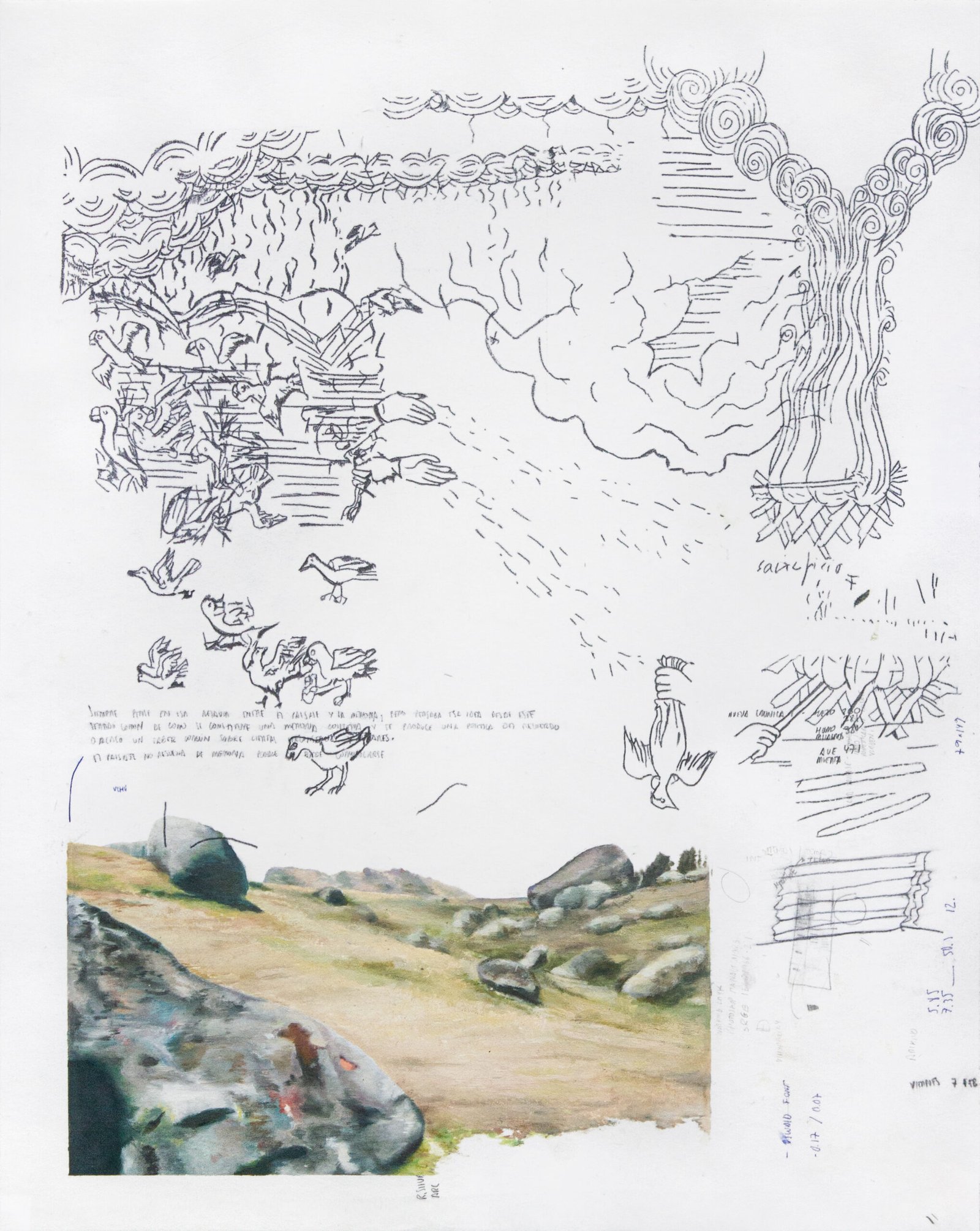

WEAK UNIVERSALISM II

In 2016, a fire in the Church of San Sebastian in Cuzco destroyed, among many works, six large-format diptychs made by the indigenous painter Diego Quispe Tito. These immense paintings in the form of lunettes that decorated the walls of the temple, were commissioned in the middle of the 17th century with the objective of serving for the evangelization of the indigenous population. Engravings sent from Europe had been distributed among the new continent to be used as models of paintings that disseminated the new model of the world and the new way of understanding history for the indigenous people. The natural world was no longer a divine space, but a pagan polytheism that had to be condemned in order to point to a god that was not in nature, but beyond it. The aforementioned series by Diego Quispe Tito was set in this context and told in images the life of St. John the Baptist, a religious preacher of the first century B.C. who used the sacrament of baptism as the center of his religious movement to initiate people into Christianity.

The interesting thing about this series of paintings was that the painted flora and fauna correspond, not to the European natural imaginary represented in the original engravings, but to the local indigenous imaginary. Animal species, wild flora or even their chromatic palette respond to another way of understanding the world. However, this process of syncretism, which could be understood as a form of resistance to the mandate of representation brought from Europe, can also be understood as a domination of the local traditional imaginary that places the story of the Christian god at the center. That is to say: what finally condenses the image is cultural domination. And this occurs because these new images anticipate the European architectural and cultural infrastructure over the indigenous ecosystem now represented.

These religious images maintain in the background a tension between civilization and nature, a marked distinction that materially anticipates a transformation of the new continent and the progressive disappearance, now total, of the indigenous culture. The failure of the Spanish viceroyalty as a political project in the 19th century did little to prevent what was already naturalized and inevitable: the introduction of the American continent into the logics of the modern world. Also with that, its geopolitical location in the stratification of the globalized world. This is another layer of a larger dispute for the progressive transformation of the world and the homogenization of the imagination; this time subject to the growth of late capitalism. What Quispe Tito’s series represents is now nothing more than a specific moment of tension suspended in history.

The project consists of producing a series of pictorial works based on the series of paintings whose photographic record is archived in PESSCA (Project on the Engraves Sources of Spanish Colonial Art). For the elaboration of the paintings, I have decided to make manual reproductions in oil on wood of the six diptychs that make up the missing series. However, this reproduction process will be carried out with the application of some instructions according to the type of image to be presented. My first guideline will be to erase all information that is not landscape or architecture; with the intention of representing images that only contemplate the tension that exists between these elements. The second slogan is to eliminate the elements of flora and fauna added by Diego Quispe Tito to the European visual model. And, the third slogan, consists of eliminating all reference to the European imaginary placed in the paintings.

WUII03.24

Dirigir

Oil and graphite on wood panel and paper

197.5x133.5cm

2024

Anunciación

Oil and graphite on wood panel and paper

193x135cm

2024

Él

Oil and graphite on wood panel and paper

162x134.5cm

2024

WEAK UNIVERSALISM

LISTE ART FAIR / CRISIS GALLERY

The project was presented in Liste Art Fair 2022 together with Javier Bravo de Rueda. The title Weak Universalism comes from the homonymous text made by Boris Groys and published in 2010. In this text, Groys reflects on the visual imaginary produced by the avant-garde as a reduction of the sign that reaches an image so simple, timeless and weak in formal terms, that it adopts the sufficient conditions to survive the timeless transformations of the modern world. This is a type of universal image accessible to anyone who can observe it.

This project approaches this idea of universalization as a tension built from the conflict to which every act of domination or interculturality is subjected. Historically, war or continental conquest —whatever its horizon— has not only become a dispute for economic and political domination, but also for the domination of the imagination. The consensuses or impositions that result from these conflicts go through a dispute for the consolidation of a new visuality. Many times, these results can be progressive, organic syncretisms of two or more forms of visual tradition; but many times they are also aggressive processes that imply a cultural eradication and extermination.

UD06.22

Photographic documentation of Crisis Booth at Liste Art Fair, 2022.

Libra 1586 / Libra 1586 (2)

Oil on wood panel

60x50cm each

2022

Mater

Oil on wood panel

60x50cm

2022

Libra 1586 (3)

Oil on wood panel

60x50cm

2022

Imagen débil, ciclo permanente 3

Oil and graphite on paper on metal sheet

120x110cm

2022

Imagen débil, ciclo permanente 2

Oil and graphite on paper on metal sheet

120x110cm

2022

Untitled

Oil and graphite on paper on metal sheet

80x100cm

2022

POR EL BIEN FUTURO

(FOR FUTURE’S SAKE) CG04.22

POR EL BIEN FUTURO

(FOR FUTURE’S SAKE) CG04.22

FOR FUTURE’S SAKE

The common sense about the differences between rural and urban areas in Peru has been built from a tension between the idea of backwardness and progress, from the paradigms of modernity and in a context of strong social and economic inequality. These relations have been historically produced since colonization, and have become more complex since the second half of the twentieth century through migratory flows from rural areas to the country’s capital. However, their relationship has also been traversed by a political class struggle with important milestones such as the agrarian reform and the internal armed conflict in the 1980s.

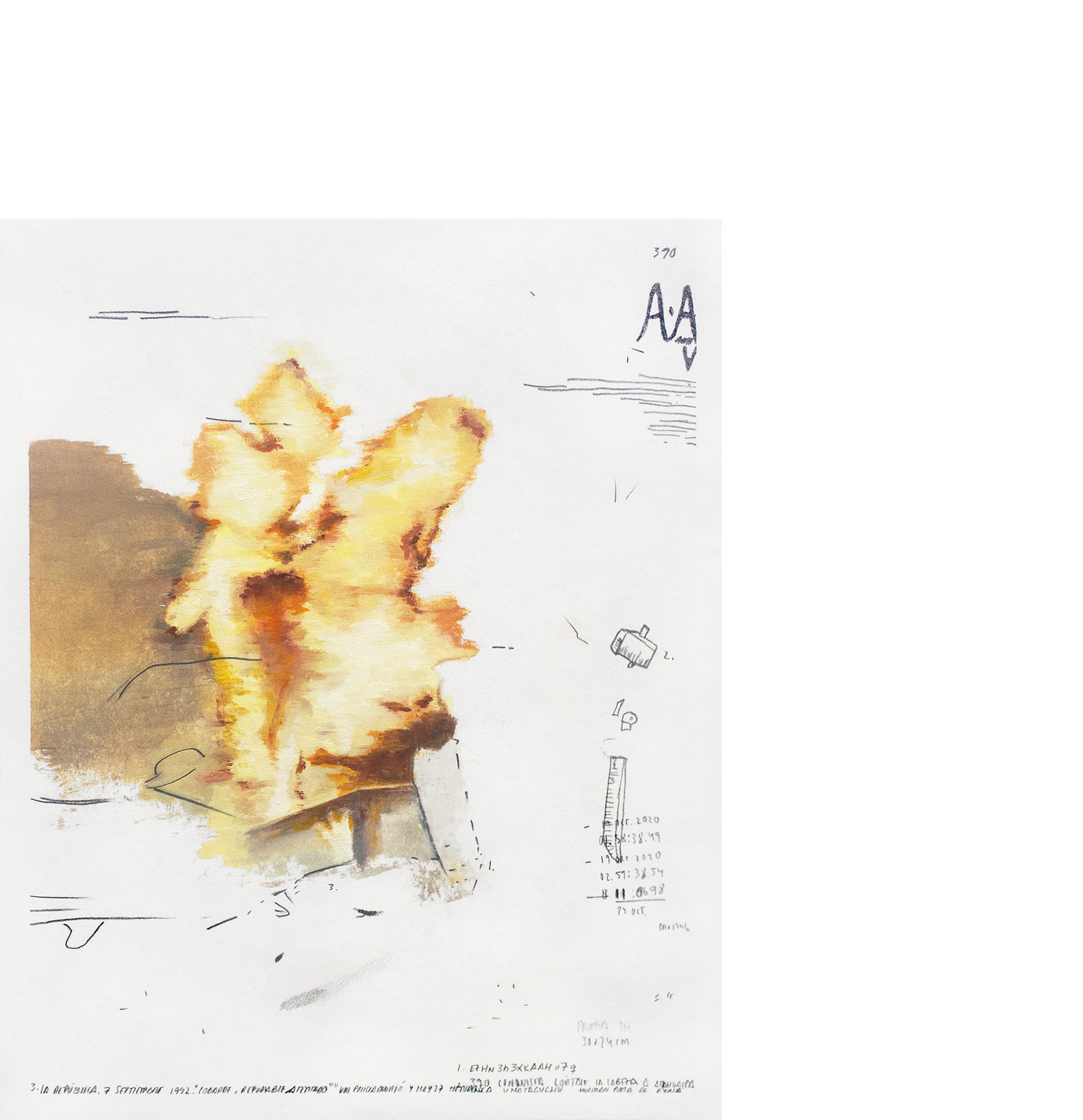

Por el bien futuro proposes a series of exercises in testimonial writing and fiction that have materialized in drawings, performance and video-performance. The textual proposal narrates the migration of my parents, their relationship with commerce and their will to progress. These testimonies are contrasted with reflections that view with skepticism certain ideas of progress inherent in me. In the course of the performance, I compare these reflections with my own artistic practice and with the exercise of automatic drawing.

FFS04.20

Stills of the video For Future’s Sake

0120-R01

Oil and graphite on paper

50x42cm

2020

0220-R01

Oil and graphite on paper

29.8x23.5cm

2020

For Future’s Sake

Offset print

42x29.7cm

2020

Photographic documentation of the lecture-performance For Future’s Sake. Fujifilm X-Space, Shangai (CHN).

Photographic documentation of the lecture-performance For Future’s Sake. Fujifilm X-Space, Shangai (CHN).

CIRCULAR GESTURES

UNANIMOUS CONSENT

Curated by Alejandra Monteverde and Alexandra Romy. «Circular time, or endless recurrences, suggest that all things iterate eternally. Circular time has no end, it is perpetually in motion. In The Gay Science, Nietzsche develops the idea of the circle of time or eternal return under the name of amor fati – the love of fate – expressing that since everything recurs infinitely in life, we shall love and embrace our fate, our infinite ways of becoming and chaos. Circular time is by definition the contrary of progress, which belongs in the realm of linear time. Progress cannot be drawn as a circle, but rather takes the shape of a line. In Western societies, progress is a way to reach a result: an obsession with perfection, forcing us on a path of advancement. We have no choice but to continuously upgrade ourselves, we must move forward, fast. It is a fashionable human aim to – ultimately – reach Paradise, and the neoliberal capitalist economies trigger us no differently. As our bodies become commodities, we are pressured to grow, consume and waste. But what if rather than categorizing time in three distinctive and extraneous units – past, present, future— we would situate ourselves, with our bodies, inside time. For the people living in the Andes, time is built differently. The past is what we can see in front of us, and the future is something that is situated behind our backs. Andean thinking literally embodies the time, using the word „eyes“ to translate the past and „back“ to translate the future. Now the perspective has changed, we are still moving, but walking backwards, observing the past and recognizing the future as something we can’t possibly see, unless we turn our head over our shoulder and have a quick glance at it. In the Andean thinking, time – alike space – is a house, a place we inhabit. It is a heartbeat, the breathing of air, the constant back and forth of the sea or the perpetual alternating between day and night, a cyclic repetition that corresponds to the order of the cosmos. Time is not a quantum that can be expressed in mathematical term or possessed, but rather is considered in its physicality, either according to its quantitative characteristics, like density, weight, or to its relational aspect, for example in connection with the importance of an event or celebration.»

*Fragments taken from the curatorial text.

CG03.22

Exhibition views of Circular Gestures, Unanimous Consent, Zurich (CH)

Detail of the video-installation For Future’s Sake at the exhibition Circular Gestures, Unanimous Consent, Zurich (CH)

RAÚL SILVA. GRACE HOPPER, 14'00'', 2025.